David Chaupis-Meza

César Cárcamo

King Holmes

Patricia García

BRIEF REPORT

Population

seroprevalence of celiac disease in urban areas of Peru

Katherine Baldera ![]() 1,

Licensed in Medical Technology with a specialty in Clinical

Laboratory

1,

Licensed in Medical Technology with a specialty in Clinical

Laboratory

David Chaupis-Meza ![]() 1,

bachelor of Science in Medical

Technology

1,

bachelor of Science in Medical

Technology

César Cárcamo ![]() 2, medical doctor, PhD in epidemiology

2, medical doctor, PhD in epidemiology

King Holmes ![]() 3, medical doctor, PhD in Microbiology

3, medical doctor, PhD in Microbiology

Patricia García ![]() 2,

medical doctor, PhD in Medicine

2,

medical doctor, PhD in Medicine

1

Escuela

de Tecnología Médica de la Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Peruana Cayetano

Heredia, Lima, Peru.

2 Unidad

de Epidemiología, ETS y VIH de la Facultad de Salud Pública y Administración,

Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

3 School

of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle,

Washington, EE. UU.

ABSTRACT

The

objective of the study was to determine the seroprevalence of celiac disease

(CD) in urban areas of Peru using a population-based sample. A random sample of

women and men 18 to 29 years old from 26 cities in Peru was screened. An

anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA kit was used for the detection of CD. Results

higher than 20 AU / ml were considered positive. The

weighted prevalence of celiac disease was 1.2% (CI 95%: 0.0% - 2.4%), thus the

estimated number of people living with CD in Peru was 341,783. CD prevalence in

Peru is similar to the world average.

Keywords: Celiac Disease; Seroprevalence; Seroepidemiologic Studies; Transglutaminases (source: MeSH NLM).

INTRODUCTION

Intolerance

to gluten (whether from wheat, barley or rye) leads to a wide spectrum of

chronic enteropathies: a) gluten allergy; b) non-celiac sensitivity to gluten

(NCSG); and c) celiac disease (CD). CD is an autoimmune disorder with a genetic

predisposition linked to the alleles HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 (1,2).

Despite its recognized characterization, its diagnosis is always elusive.

When compared to CD, NCSG shows no association with any genetic or

immunological alteration, nonetheless both conditions present a similar

clinical picture. This seems to be due to the fact that a gluten-derived

fragment, alpha-gliadin, would be the main target epitope associated with

duodenal disorders present in both CD and NCSG (3).

Depending on its clinical presentation, CD can present evident

symptoms (diarrhea, steatorrhea, fatigue, dyspepsia, and malnutrition), an

extragastrointestinal clinical picture (iron deficiency anemia, fatigue,

depression, peripheral neuropathies, and cerebellar ataxia), or an asymptomatic

picture

(4), often detected by routine serological screening or by its

association with chronic complications such as malignant lymphomas (5).

Worldwide, the prevalence of CD is 1%, with a female:male ratio of 2.8:1. It is assumed that Latin America and

Europe have similar prevalence of CD, which may vary between 0.46 and 0.64% (6).There

are no population-based studies of prevalence in Peru, but there are clinical

cases of CD that warn of the need for national serological mapping of the

disease (7,8,9).

|

KEY MESSAGES |

|

Motivation for the study:

Celiac disease has different clinical presentations, being the undiagnosed

cases the larger group yet to be recognized. A serological screening can be

an early detection test for celiac disease; furthermore, it would avoid fatal

complications.

Main findings:

This is the first

“extra-nosocomial” population-based study in Peru. A prevalence of celiac

disease of 1.2% was found using the IgA tissue antitransglutaminase test.

Implications:

Further population-based studies of celiac disease in Peru are recommended. |

These tests

detect antibodies that are reactive to gluten (IgA and/or IgG), such as

anti-endomysial antibody (EMA), anti-glia-din antibody (AGA), and anti-

transglutaminase antibody (tTGA). The latter is used for the early detection of

CD at any age, which is then confirmed by an intestinal biopsy (10).

The purpose of the study was to determine the seroprevalence of CD in urban

populations of Peru using a population-based sample.

THE STUDY

Subjects and study population

The study uses demographic and biological sampling information

from the PREVEN study (11), which included women and men between

18 and 29 years old in 26 cities in Peru, selected through a multi-stage

cluster sampling in households located in urban areas. Our study selected 1,208

samples by simple random sampling from 17,293 samples collected between 2005

and 2007 by the PREVEN study. Participants completed an epidemiological

questionnaire and provided biological samples. The serum obtained was stored at

–20 °C in the serum bank of the Research and Development Laboratories (LID) of

Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH).

Sample processing

Hemolyzed,

lipemic samples were discarded; as well as cryovials with insufficient

remaining volume (<10ul) of serum or samples without epidemiological

information. The samples were processed by colorimetric enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The IgA tissue antitransglutaminase kit (Diametra

Diagnostic, Italy) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol, which has

a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 95% (12). The samples and the reagent

kit were defrosted at room temperature for about 30 minutes. One positive and

one negative control were included. The samples were diluted 1:10 and placed in

microwells coated with recombinant tissue transglutaminase. They were incubated

for 30 minutes at room temperature.

The supernatant was discarded and the microwells were washed

three times to remove the remaining unbound components. Anti-human IgA

conjugate marked with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was then added and incubated

for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing, the excess conjugate was removed,

the substrate was added with trimethylbenzidine (TMB) and incubated for 15

minutes at room temperature protected from the light. The reaction was stopped

with sulphuric acid.

The sample

reading was made with a 450 nm filter and a 650 nm reference filter. As a

confirmatory test, those samples with results >20 AU/ml were subjected to a

second ELISA following the same procedures described. Those samples in which

the second ELISA showed values >20 AU/ml were considered positive. Samples

with ≤20 AU/ml values in the first or second ELISA were considered negative.

Statistical Analysis

For each

sample included in the study, an expansion factor was calculated, corresponding

to the inverse of the probability of participation. The probability of

participation was the product of several probabilities: the probability of

selection of the cluster within the city, the probability of selection of the

dwelling within the cluster, the probability of selection of the participant

within the dwelling, and the probability of selection of the individual for

participation in the present study. Estimates were also adjusted for city level

stratified sampling. Weighted prevalence is presented, with its respective

confidence intervals. Pearson’s chi-square test for weighted samples was used

for the comparison of proportions. Stata 8.2 (College Station, Texas) was used

for all calculations.

Ethical aspects

Participants provided verbal consent for their participation in

the study. The original study’s informed consent form contemplated the storage

of samples for future studies without the inclusion of personal identifiers. As

part of this study, only codes were used to identify the samples and link them

to their epidemiological information. The present study was approved by the

Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia

(code SIDISI 60226).

RESULTS

Out

of the 1,208 selected samples, 107 were discarded for being hemolyzed (73),

lipemic (1), insufficient volume (18) and lack of epidemiological information

(15). Finally, 1,101 samples were incl44uded in the analysis, of which 420 were

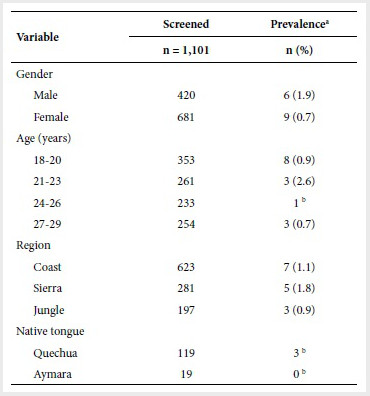

male and 681 were female (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the 1,101

participants selected

a Weighted prevalence; b could not

be calculated as there was only one

A weighted prevalence of CD of 1.2% (95% CI 0.0-2.4) was

obtained. The sample is representative of 3,399,734

people aged 18-29 years, living in urban areas in Peru. Thus, it is estimated

that in this population there are 40 797 people with CD (95% CI: 0-81 594).

Although the weighted prevalence in women (0.7%) was lower than

in men (1.9%), this difference is not statistically significant (p=0.253).

Similarly, the prevalence in the 21-23 age group is higher than for other age

groups, no statistically significant difference is found (p=0.144).

Of the total number of individuals, 623 lived in the coastal

region, 281 to the sierra and 197 to the jungle. The prevalence of CD in the

sierra (1.8%) was not significantly higher than that found on the coast or in

the jungle (1.1 and 0.9%, respectively).

Although

few participants spoke Quechua or Aymara (119 and 19, respectively), no

statistically significant differences were found in the prevalence of CD

between these and the rest of the participants in the study (p=0.288 and

p=0.811, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This

is the first study in Latin America to evaluate the prevalence of CD by

serological screening for tissue antitransglutaminase IgA in a population-based

sample, and a prevalence of 1.2% was found. If the prevalence for other ages

and geographical areas of the country in 2007 had been the same, then it is estimated

that for that year the number of people living with celiac disease in Peru was

341,783.

In the United States, the prevalence of undiagnosed CD is

increasing. A study determined the presence of IgA tissue antitransglutaminase

in stored samples (for at least 20 years at –20 °C), to determine changes in

prevalence over a 50-year period (13). Samples taken between 1948

and 1954 showed a prevalence of 0.2% and those taken between 1995 and 2003

showed a prevalence of 0.8%, both in adults over 50 years. On the other hand,

in samples of persons aged 18 to 49 taken between 2006 and 2008, a prevalence

of 0.9% was found. Previously in the mentioned study the presence of IgA was

revealed in the old samples using nephelometry.

Another study conducted in Argentina (14), using AGA (IgA and

IgG) and EmA (IgA) as serological markers, determined a CD prevalence of 0.6%.

Our study reveals a higher prevalence, probably because of the age group and

the type of serological test used. On the other hand, a study in Brazil (15) in people of 18-65 years old without anemia

found a prevalence of 0.33% using the anti-TBM IgA and anti-EmA IgA test. The

low prevalence found may respond to the fact that anemia is an atypical

presentation of CD.

Epidemiological studies exploring the population risk of

presenting CD are scarce in Latin America (6). In Peru, the few clinical

reports that exist warn of the presence of CD in a “low frequency” and linked

to the classic type of the disease (7-9,16).

Serological screening for CD is recommended instead of the use of

invasive methods such as biopsies, being an early diagnostic choice to rule out

CD. According to ESPGHAN (European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition) (17), the diagnosis of CD can be confirmed

with anti-transglutaminase levels above ten times the upper normal limits (≥20

U/ml, reference value for our study), this levels are compared to Marsh-3 type

villous atrophy. This emphasizes the usefulness of the IgA tTGA serological

test as the most reliable serological marker for CD, not only because of its

high specificity and sensitivity, but also because of its usefulness, as

samples can be stored for extended periods of time,being

possible to reuse them in cryopreserved samples (18), as in our case.

Indeed, having a reliable serological test would allow for a reduction in costs

and time in the diagnosis of CD.

The absence of information on gastrointestinal symptoms and

history of CD could constitute a limitation of the present study, however, the

clinical correlation of serology is quite well known.

Our study found a higher prevalence of CD in people from the

sierra. This could correspond to genetic differences, or to environmental

factors, such as height and consequent hypoxia. Although other studies have

found higher prevalence in women (6), our study found higher

prevalence in the male population, a difference for which we found no cause.

In

conclusion, the present study is the first to be carried out in Peru based on a

population sample of young adults, showing a higher prevalence than reported in

other studies of the American continent, but similar to the world average. More

studies of seroprevalence in populations that are atypical for CD are

suggested, taking into account the different forms of clinical presentation,

since in most cases celiac disease has no apparent symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C,

Dolinsek J, Green PHR, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Spectrum of

gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC

Med. 2012;10:13.

2. Elli L, Branchi F, Tomba C,

Villalta D, Norsa L, Ferretti F, et al. Diagnosis of gluten related

disorders: Celiac disease, wheat allergy and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(23):7110–9.

3. Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF,

Green PHR. Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ. 2015;351:h4347.

4. Rashid M, Lee J. Serologic

testing in celiac disease: Practical guide for clinicians. Can Fam Physician

Med Fam Can. 2016;62(1):38–43.

5. Kelly CP, Bai JC, Liu E,

Leffler DA. Advances in diagnosis and management of celiac disease.

Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1175–86.

6. Parra-Medina R,

Molano-Gonzalez N, Rojas-Villarraga A, Agmon-Levin N, Arango M-T, Shoenfeld Y, et

al. Prevalence of celiac disease in latin america: a systematic review and

meta-regression. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0124040.

7. Vera A, Frisancho O, Yábar

A, Carrasco W. Enfermedad Celiaca y Obstrucción Intestinal por Linfoma de

Células T. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2011;31(3):278–81.

8. Llanos O, Matzumura M,

Tagle M, Huerta-Mercado J, Cedrón H, Scavino J, et al. Enfermedad

celiaca: estudio descriptivo en la Clínica Anglo Americana. Rev Gastroenterol

Peru. 2012;32(2):134–40.

9. Tagle M, Nolte C, Luna E,

Scavino Y. Coexistencia de Enfermedad Celíaca y Hepatitis Autoinmune. Reporte

de un caso y revisión de la literature. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2006;26(1):80–3.

10. Rostom A, Murray JA,

Kagnoff MF. Medical Position Statement on Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology.

2006;131(6):1977–80.

11. García PJ, Holmes KK,

Cárcamo CP, Garnett GP, Hughes JP, Campos PE, et al. Prevention of

sexually transmitted infections in urban communities (Peru PREVEN): a

multicomponent community-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1120–8.

12. Kowalski K, Mulak A,

Jasinska M, Paradowski Leszek. Diagnostic challenges in celiac disease. Adv

Clin Exp Med. 2017; 26(4): 729–37.

13. Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson

JF, Choung RS, Brantner TL, Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, et al. Increased

mortality among men aged 50 years old or above with elevated IgA

anti-transglutaminase antibodies: NHANES III. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):136.

14. Gomez JC, Selvaggio GS,

Viola M, Pizarro B, la Motta G, de Barrio S, et al. Prevalence of celiac

disease in Argentina: screening of an adult population in the La Plata area. Am

J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(9):2700–4.

15. Melo SBC, Fernandes MIM,

Peres LC, Troncon LEA, Galvão LC. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of

celiac disease among blood donors in Ribeirão Preto, State of São Paulo,

Brazil. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(5):1020–5.

16. Arévalo F, Roe E,

Arias-Stella-Castillo J, Cárdenas J, Montes P, Monge E. Low serological

positivity in patients with histology compatible with celiac disease in Perú.

Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102(6):372–5.

17. Smarrazzo A, Misak Z,

Costa S, Mičetić-Turk D, Abu-Zekry M, Kansu A, et al. Diagnosis of

celiac disease and applicability of ESPGHAN guidelines in Mediterranean

countries: a real life prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):17.

18. Wengrower D, Doron D,

Goldin E, Granot E. Should stored Serum of Patients Previously Tested for

Celiac Disease Serology be Retested for Transglutaminase Antibodies?. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(9):806-8.

Funding:

Fundación Instituto Hipólito Unanue.

Citation:

Baldera K, Chaupis-Meza D,

Cárcamo C, Holmes K, García P. Seroprevalencia poblacional de la enfermedad

celíaca en zonas urbanas del Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica.

2020;37(1):63-6. Doi: https://doi. org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4507.

Correspondence to:

David

Chaupis Meza; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; Av. Honorio Delgado 430,

Lima 31, Peru;

david.chaupis.m@upch.pe.

Authorship

contribution: KB participated in the technical execution,

data analysis and obtained the funding for the study. DCM participated in the

conception and design of the study, interpretation of the results and writing

of the first version of the manuscript. CC participated in the statistical analysis

and interpretation, critical review and writing of the final version of the

article. Both KH and PG are the principal investigators of the PREVEN study.

All the authors finally approved the last version of the article.

Conflicts

of interest:

All authors have none to declare.

02/05/2019

Approved:

29/01/2020

Online:

23/03/2020