Jonh Astete-Cornejo

Fernando G. Benavides

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Working, safety

and health conditions in the economically active and employed population in

urban areas of Peru

Iselle Sabastizagal-Vela

![]() 1,2,

Psychologist,

Master in Occupational Health

1,2,

Psychologist,

Master in Occupational Health

Jonh Astete-Cornejo

![]() 1,2, medical specialist in

Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Master in Business Administration with

specialization in Integrated Quality, Safety and Environmental Management

1,2, medical specialist in

Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Master in Business Administration with

specialization in Integrated Quality, Safety and Environmental Management

Fernando G. Benavides

![]() 3,4, medical

specialist in Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Doctor of Medicine.

3,4, medical

specialist in Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Doctor of Medicine.

1 Instituto Nacional de Salud, Lima,

Peru.

2 Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia,

Lima, Peru.

3 Centro de Investigación en Salud

Laboral (CiSAL), Barcelona, España.

4 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Parc Salut

Mar, Barcelona, España.

ABSTRACT

Objetives: The present study aims to know the work, safety and health

conditions at the jobs of the economically active urban population in Peru.

Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out based on a probabilistic

sample of multistage areas in which 3122 people over 14 years of age

distributed nationwide participated.

Results: The majority were men (53.6%) between 30 and 59 years (50%). As

for working conditions, most people work more than 48 hours per week (39.8%),

and Monday through Saturday (44.7%). Regarding the safety, hygiene, ergonomic

and psychosocial conditions, the results showed a lower risk exposure.

Regarding health conditions, the majority report that the identification and

evaluation of occupational hazards is not carried out in their workplace

(35.9%), they do not have occupational health services (40.7%) or a delegate or

a Health and safety committee (39.4%) and no occupational medical evaluations

(39.3%).

Conclusions: The economically active urban population of Peru is more

frequently exposed to noise, solar radiation, awkward postures and repetitive movements,

work at a fast pace with little control and hide their emotions; In addition,

occupational health is not managed adequately in workplaces. These conditions

may affect the health of workers and the quality of work.

Keywords: Working Conditions; Occupational Risks; Employment; Occupational Health (Source: MeSH NLM).

INTRODUCTION

Employment

generates economic and social growth and affects workers’ health and

well-being, i.e. it can be a source of improvement or harm. Paid work is the

main source of income for most people, and it is a strong component of their

social identity (1).

Workers are exposed to conditions that affect their

health, either positively or negatively. Such conditions involve the characteristics

of the work organization, its environment and immediate surroundings, which can

be considered physical, chemical, psychosocial, mechanical, and environmental

risk factors, among others. Therefore, occupational health and safety

conditions are established in organizations, these are related to the

implementation of measures to eliminate or reduce the risk of suffering

injuries, damaging health, material damage to equipment, machines or

infrastructure. Similarly, workers’ health management, and preventive

activities and resources involved within the organizations, are included (1,2).

Therefore, a worker with adequate working, safety

and health conditions is strongly identified with the organization’s policies

which are strengthened, as well as his or her motivation and productivity. On

the contrary, if the workplace has precarious conditions, the workers’ health

could be affected, in addition to the previously mentioned aspects, which

generates a high social cost (2).

According to the International Labor Organization,

there is a high frequency of deaths caused by work accidents or diseases,

related to poor occupational safety and health practices. These health issues

generate a high social and economic cost, due to losses related to working

time, production development, medical care and rehabilitation of workers, as

well as the payment of compensation (3,4).

On the labor aspect, Peru maintained an economic

growth that allowed a 2.4% increment of formal employment from April 2013 to

March 2014 (5),

and Metropolitan Lima showed a variation of 6.6% during first quarter 2019 (6). In addition, under the Occupational Safety and Health Act,

employers must create means and conditions to protect workers’ health and

safety (7)

by developing management systems according to their needs, and

report to the Ministry of Labor any occupational accidents and diseases that

occur in their organizations (8).

|

KEY MESSAGES |

|

Motivation for the study:

To know the working, safety and health conditions of the urban

economically active occupied population of Peru.

Main findings:

The

urban economically active occupied working population is more frequently

exposed to noise, solar radiation, uncomfortable postures and repetitive

movements; they work fast with little control and hide their emotions;

moreover, occupational health is not managed in the workplace. These

conditions can affect workers’ health and the quality of their work

Implications: Knowing working and health conditions of the economically

active population will allow the establishment of guidelines for improvement

within the framework of the Law on Safety and Health at Work |

Occupational surveys on working conditions are

valuable tools for obtaining information to develop strategies for promoting

health and preventing negative events for working groups. These surveys are

useful for monitoring workers’ health (9), and working, employment and

health conditions worldwide.

As indicated in the National Plan for Occupational

Safety and Health 2017-2021 (8), there are national statistics on occupational

accidents and diseases; however, they do not express all of the occurrences,

nor do they record the working conditions of the economically active population

(EAP). For this reason, the aim of the present study was to determine the

safety and health conditions at work of urban economically active occupied in Peru,

by applying a population survey.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

Study Design

A

cross-sectional design study based on a probability sample associated to

geographical areas, in which the likelihood of being selected is associated

with geographical areas in the scope of study, which is also multi-stage. The

sample was designed to give reliable estimates at the national urban level.

Sample Framework

The

sample framework was obtained from the statistical information of the National

Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI in Spanish), from the 2007 Census

and updated with information from the Household Targeting System (SISFOH in

Spanish) 2012-2013, a system used by the INEI for conducting population surveys

(10).

The population comprises the habitual residents, over 14 years old, from urban

private dwellings nationwide. The sample used was requested from the INEI,

which included clusters with information on blocks, dwellings, population and EAP

from 252 districts of Peru.

Participants

Residents of urban areas of Peru, over 14 years old, who work or

have worked, at least for one hour, the week before the survey or who are

temporarily absent from work due to vacation, illness, leave, etc. (11).

Children under 14 years old and those children whose surveys showed errors in

completion were excluded.

Sample

The sample was probabilistic, area-based,

stratified and multi-stage. With a known population and applying the proportion

formula with a confidence level of 95%, a permissible error of 2.7%, a

non-response rate of 10% and a design effect of 1.2. The calculated sample was

3,120 persons distributed in 520 clusters.

The sampling was carried out in several stages.

First stage: selection of clusters with probability proportional to the size of

the households (clusters: group of households defined by the INEI that include

approximately 100 to 150 households). Second stage: selection of blocks within

each cluster (systematic random sampling with random start). Third stage:

random selection of households in the selected blocks (random sampling through

a random number chart). Fourth stage: random selection of the person to be

interviewed. The unit of analysis was the working person, selected among people

who work in each household.

Variables

Socio-demographic variables, such as sex, age, education, job,

economic activity of the company and number of workers. Working conditions,

including employment conditions (weekly working hours, working days, type of

relationship, contract, form of contract, type of workday, remuneration), other

conditions such as safety, hygiene, ergonomic and psychosocial factors,

resources and preventive activities (information or training on occupational

risks, evaluations, measurements or controls of possible risks, access to

occupational health services, occupational health and safety or hygiene

committee, occupational medical examination, and workers participation). Health

conditions, such as the perception of health, as well as injuries, and

occupational diseases.

Instrument

The Basic Questionnaire on Working, Employment and

Health Conditions in Latin America and the Caribbean (CTESLAC in Spanish) (12,13) provides

information on workers’ perceptions of working, employment and health

conditions in their workplaces. It has 77 questions which include

socio-demographic characteristics, employment conditions, work, health,

resources, and preventive occupational health activities in the work centers,

and family characteristics of the respondents. It was developed by the Network

of Experts on Surveys of Working, Employment and Health Conditions (RED ECTS in

Spanish), based on surveys of working conditions used in Spain, Colombia,

Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Central America, in order to improve the

comparability of survey results in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The

answers to the questions include: frequency of the condition (always, several

times, sometimes, very few times and never; or if it presents or not a certain

condition), the completion time of the questionnaire is of 25 minutes and the

results are expressed according to the answer options.

For this study, a group of 34 experts in

occupational health (doctors, psychologists, nurses and medical technologists)

reviewed and adapted the questionnaire. They discussed the relevance of each

item, and the application of a pilot questionnaire to 34 workers in Lima, Ica

and Arequipa. The partial response rate (i.e., the omission of information in

some of the questions) (14) was 3.2%.

An

acceptable correlation was found in safety (0.52-0.77), hygiene (0.29-0.50) and

ergonomics (above 0.3). However, the psychosocial aspect showed a low

correlation (less than 0.3). Overall, the questionnaire has a high reliability

of the safety, hygiene and ergonomic aspects (15). It is important to point

out that, regarding the correlation of psychosocial conditions, we consider

that it does not affect the gathering of information, since the questionnaire

is not a diagnostic instrument and therefore allows for the collection of

relevant information on working conditions.

The final version of the questionnaire consists of

three filter questions and 87 Likert-scale questions. An adequately trained

interviewer applied the questionnaire to the participants in their homes, with

an average duration of 20 minutes.

Procedure and

statistical analysis

The information-gathering phase took place from

November 2016 to June 2017. The process was gradual and on different dates,

however, it was simultaneous at some points. For this purpose, experienced

surveyors were called in, and the team of researchers trained them in

occupational health, working conditions, handling the questionnaire and

selecting the respondents in the field. The questionnaire was printed on paper

and applied to each participant.

For

the selection of the household, in each cluster (according to the criteria of

the INEI, as a

subpopulation, which has characteristics present in

the population, with attributes such as geographical location, being over 14

years old, worker (16)), the following procedure was taken into account: at

random, in each block, the households were selected (nine households, of which

three were replacement households, in the event that a possible participant was

not identified), and then, for the random selection of the occupied EAP member,

within the households, the Kish (or random) chart was used.

To calculate the confidence intervals (sampling

errors), the statistical program SPSS 20, complex samples section, was used,

which provides the sample variability estimators for population parameters (the

elaborated frequency plan contained: the file plan, the frame stratum, the

cluster and the expansion factor by district, for the construction of the

expansion factors, the selection probabilities in each stage were taken into

consideration), such as totals, means, ratios and proportions for the different

estimation domains, and the algorithm used by SPSS is based on the method of

the variance estimators of the final clusters (17).

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Institutional Committee of Ethics

and Research of the National Institute of Health. Informed consent (assent for

those under 18 years old) was applied, which was codified and guarded by the

research team.

RESULTS

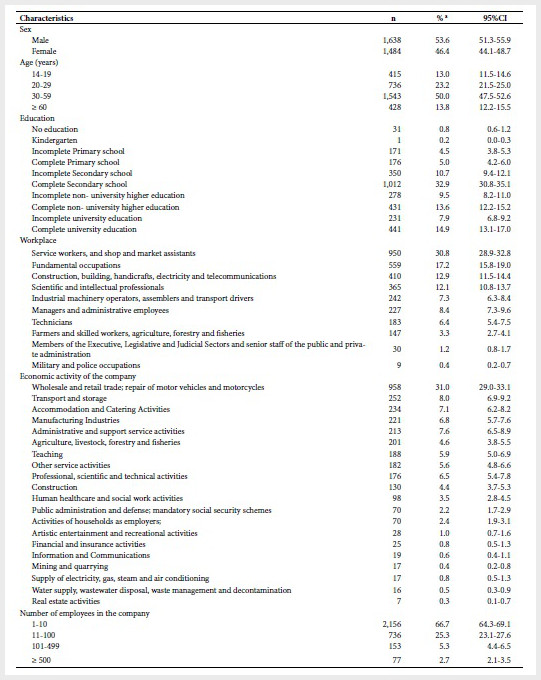

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics, jobs,

economic activity and number of workers in the company, Peru, 2017

95%CI: 95% Confidence Intervals

a Weighted percentages according to expansion factors

In terms of employment, most were service workers

and shop and market assistants (30.8%), from wholesale and retail trade sector,

in the repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (31.0%), and worked in small

centers, that is, between 1 and 10 persons (66.7%).

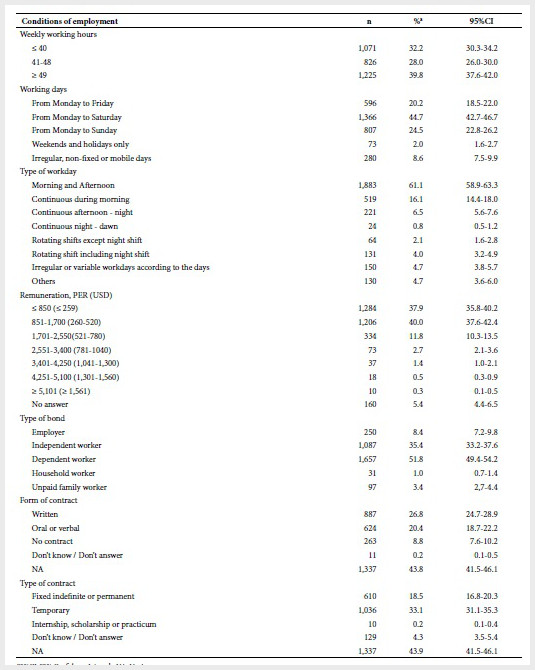

Regarding working conditions (Table 2), 39.8%

worked 49 hours or more per week; 44.7% worked from Monday to Saturday; and

61.1% worked split shifts, morning and afternoon. Regarding the net monthly

income of the participants, the highest percentage received remuneration

between 851 soles and 1,700 soles (40%); 51.8% were dependent workers; and

regarding the form and type of contract, 26.8% had a written contract and 33.1%

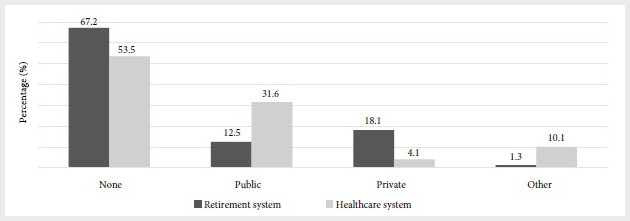

a temporary contract. With respect to the social protection coverage of the

interviewees, 67.2% said that they did not contribute to any retirement system

and 53.5% did not have any health insurance (Figure 1).

Table 2. Employment conditions by weekly working

hours, working days, type of workday, remuneration, role, contract and type of

contract in workers in Peru, 2017

95%CI: 95% Confidence Intervals, NA: No Answer

1 USD= 3,27 PER (change rate for 2017)

a Weighted percentages according to expansion factors

Figure 1. Employment conditions by social protection

coverage according to the pension system, 2017

With respect to exposure to occupational risk

factors, less than 6.5% of those surveyed indicated that they are often or

always exposed to falls at the same or lower levels; more than 7% of workers

reported that they are often or always exposed to a level of noise that forces

them to raise their voice to talk to another person and more than 8% reported

that they are oftenor always exposed to solar radiation for a minimum period of

one hour per day. Their tasks make them keep uncomfortable or forced postures

(12.9%) or to make repetitive movements (21.6%). Psychosocially, they must work

very fast (13.9%) and hide their emotions or feelings when doing their work

(12.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Working conditions according to safety,

hygiene, ergonomics and psychosocial aspects of workers in Peru, 2017

SC: safety conditions; HC: hygiene conditions; EC: ergonomic

conditions; PC: psychosocial conditions; DK/DA: don’t know / don’t answer

a Weighted percentage according to expansion factors.

b Do you work in environments with unstable, uneven and/or slippery

floors, which may cause you to fall?

c Do you work in environments with surfaces with holes, stairs

and/or unevenness that can cause you to fall?

d Do you use equipment, instruments, tools and/or work machines

that can cause you damage or injury such as cuts, blows, scratches or scrapes,

punctures, amputations, etc.?

e Are you exposed to a level of noise that forces you to raise your

tone of voice when talking to others?

f Do you inhale chemicals in the form of dust, fumes, aerosols,

vapors, gases and/or mist? It does not include tobacco smoke.

g Do you handle, or are you in contact with, animals or people who

may be infected, or contaminated materials such as garbage, body fluids,

laboratory equipment, etc.?

h Are you exposed directly to the sunlight or radiation for at

least 1 hour a day?

i Do you perform tasks that force you to maintain uncomfortable or

forced postures (positions)?

j Do you lifts, move, push or pull loads, people, animals or other

heavy objects?

k Do you perform tasks that require you to make repetitive

movements?

l Do you have to work very fast?

m Does your job demands that you have to control many things at

once?

n Does your job require you to hide your emotions or feelings?

o Does your job allow you to apply your knowledge and/or skills?

p Does your

job allow you to learn new things?

q Do you have any influence on the amount of work you are given?

r Think about all the work and effort you put in. Do you think the

recognition you receive at work is appropriate?

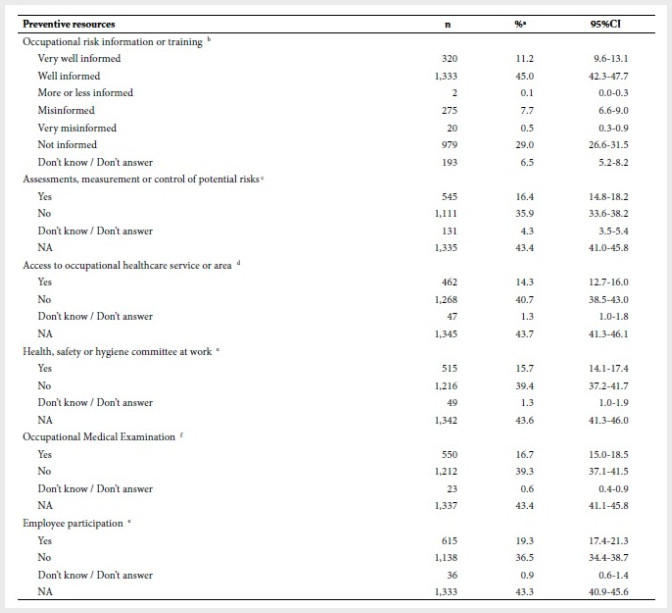

With regard to resources and preventive activities,

7.7% of the workers reported having received poor information about

occupational risks. With regard to the identification and evaluation of

occupational risks, 35.9% of the dependent workers did not have a risk

evaluation for their job in the last 12 months; 40.7% did not have an

occupational health service or area in their work center; 39.4% did not have a

prevention delegate or supervisor or an occupational health and safety or

hygiene committee; 39.3% did not have an occupational health examination in the

last 24 months, and 36.5% indicated that their work center did not hold regular

meetings to discuss health and safety issues (Table 4).

Table 4. Resources and preventive activities and

identification and evaluation of occupational risks for workers in Peru, 2017

95%CI: 95% confidence intervals, NA: No answer

a Weighted percentages according to expansion factors.

b Are you informed about the risks to your health and safety

related to your work?

c Do you know if any assessments, measurements or monitoring of

potential health risks have been carried out in your workplace during the last

12 months?

d Do you have access to an occupational healthcare service or area

at your workplace?

e Is there a delegate, supervisor, health, safety or hygiene

committee in your workplace?

f Have you had an entry, periodic or retirement medical

occupational examination in your workplace during the last 24 months?

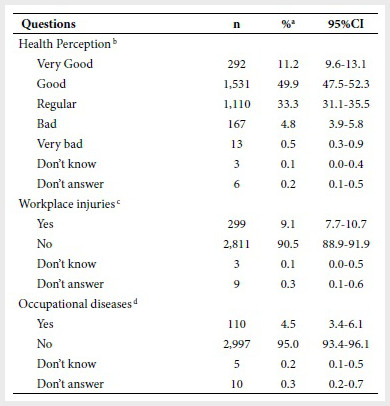

Finally, regarding the participants’ perception of

their health in general, the majority (49.9%) responded that their health was

good. A total of 9.1% reported that they had suffered some injury or damage due

to an accident at work, and 4.5% reported that they had suffered from one or

more diseases caused by work (Table 5).

Table 5. Perception of health, injuries and

occupational diseases in workers in Peru, 2017

95%CI: confidence intervals

a Weighted percentages according to expansion factors.

b In the last two weeks, in general, which of the following

statements reflect your health state?

c During the last 12 months, have you suffered any injury or damage

due to an accident at work?

d During the past 12 months, have you suffered from one or more

illnesses diagnosed by a doctor, caused by work?

DISCUSSION

Peru’s urban occupied active population has a profile

characterized by a high percentage of workers with long working hours, low

social protection coverage (the highest percentages of workers were not

registered in any retirement plan or health system), and independent workers

have long working hours, low pension coverage and low economic income. These

situations can affect workers’ health and performance, as well as the quality

of their work, which could be related to informality or precariousness of

employment. These results are different from those reported in Colombia (18),

Argentina (19),

Chile (20)

and Central America (21), where most workers do have

these systems.

A total of 9.2% of participants always work in noisy

environments, a frequency of exposure lower

than the observed in other countries of the region (19-21),

which in general exceed 15%. This differs to the report made in 2017, when

59.2% of the occupational illnesses notified to the Ministry of Labor and

Employment Promotion (MTPE in Spanish) of Peru (22) were due to hearing loss or deafness caused by

noise. However, this higher percentage of hearing-related illnesses may be

explained by a lower quantity of reported cases from other pathologies.

Between 9.1% and 21.6% of surveyed subjects suffer

from uncomfortable postures, they lift or move loads, or make repetitive

movements. These figures are lower than those observed in the surveys carried

out in Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Central America and Uruguay (23).

However, no musculoskeletal diseases related to such exposure were reported in

the MTPE (22) during 2017. Regarding psychosocial conditions,

between 12% and 41% of the population surveyed said that they always work too

fast or hide their emotions, or that they never influence the amount of work

assigned to them, similar to that found in surveys in other countries (19-21).

It should

also be noted that this is the first time that Peru gets information on

prevention and resources from companies, which, according to the regulations (7),

they are the ones that must carry out these preventive activities. The surveyed

subjects report that their work organizations do not identify nor evaluate

occupational risks at workplace, provide occupational health service, consider

a prevention delegate or supervisor at the workplace, provide annual

occupational medical evaluations. These reported information by the subjects

can be explained by the fact that not all employers have implemented the

guidelines of the Occupational Safety and

Health law in their organizations, or, that workers are not correctly

informed about it.

As for the perception of health, this is similar to

that found in the surveys of Colombia, Chile and Central America, which

perceive, in a high percentage, that their workers are healthy, and have a low

percentage of accidents and occupational diseases. Similar to what was found in

the National Socio-economic Survey about Access to Health from EsSalud Insured

Persons in Peru (24), which indicates that 64.1% of the insured population

refers having no symptoms, illness or accident.

Among the advantages of this study, it should be

mentioned that, in order to obtain the information, the surveys were applied in

the households, having as a common filter people who had worked, at least one

hour, in the week prior to the interview. Unlike the surveys carried out in

Colombia (18),

Argentina (19),

Chile (20) and Uruguay (23), where the interviews took

place in the formal workplaces.

Among the limitations, it should be mentioned that

the information collected has not been verified. That is, the instrument

collects the perceptions of the workers and this information is based on their

honesty (we do not verify the conditions in their workplaces), which is common

in this kind of study. Similar surveys were conducted in the European Union

since 1990, every five years (25). However, and despite the fact that

information was not verified, this study provides for the first time a

description of the working, employment and health conditions in a

representative sample of the occupied active population in urban areas of Peru.

In conclusion, there is ample room for occupational

risk prevention among Peru’s urban occupied

economically active population, especially among dependent workers with

long working hours, low social protection coverage and low economic income,

poor occupational health management in their workplaces; situations that might

affect their health and performance, as well as the quality of their work.

This first task provides the basis for monitoring

and surveillance of the working, employment and health conditions of the urban

occupied active population in Peru. Similar studies should be carried out

periodically. In addition, occupational health information should be

disseminated to raise awareness in the workers (independent and dependent) and

their employers in order to reduce exposure to occupational risks and prevent

work-related accidents and diseases.

Acknowledgements:

To the district authorities and to the EAP participating in the study. To Miguel Burgos, for his support in editing the manuscript and to the postgraduate collaborators in Occupational Health, Occupational Medicine and Environment of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, for their support in the process of adaptation and application of the questionnaire

REFERENCES

1. Neffa

JC. Los riesgos psicosociales en el trabajo: contribución a su estudio

[Internet]. Buenos Aires: Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones Laborales

CEIL-CONICET; 2015. 550 p. [citado el 19 junio 2019]. Disponible en: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/fo-umet/20160212070619/Neffa.pdf.

2. Neffa

JC. ¿Qué son las condiciones y medio ambiente de trabajo? Propuesta de una

perspectiva [Internet]. Buenos Aires: Hvmanitas-Ceil;

2002. [citado el 5 junio 2019] Disponible en: http://www.referato.com/uba-proceso-2/neffa_Condiciones_y_medio_ambiente_de_trabajo.pdf.

3. Levaggi

V. ¿Qué es el trabajo decente? [Internet]. Ginebra: Organización Internacional

del Trabajo; 2004 [citado el 11 Sep 2015]. Disponible

en: https://www.ilo.org/americas/sala-de-prensa/WCMS_LIM_653_SP/lang--es/index.htm.

4. International Labour Organization. Safety and health at work: A vision for sustainable

prevention. XX World

Congress on Safety and Health at Work 2014 [Internet].

Geneva: ILO, 2014 [citado el 14 octubre 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_301214.pdf.

5. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Informe técnico de la situación del mercado laboral

en Lima Metropolitana [Internet]. Lima: INEI; 2019 [citado el 1 julio 2019].

Disponible en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/04-informe-tecnico-n04_mercado-laboral-ene-feb-mar2019.pdf.

6. Ministerio de Trabajo y

Promoción del Empleo. Avance de los Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de

Variación Mensual del Empleo (ENVME), marzo 2014 [Internet]. Lima: MTPE; 2014.

[citado el 20 mayo 2019] Disponible en: https://www.trabajo.gob.pe/archivos/file/publicaciones_dnpefp/2015/AVANCE_ENVME_Marzo_2014.pdf.

7. Reglamento de la Ley No 29783, Ley de Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo.

Decreto Supremo N° 005-2012-TR [Internet]. Lima: Congreso de la Republica; 2012

[citado el 20 mayo 2019]. Disponible en: http://www.munlima.gob.pe/images/descargas/Seguridad-Salud-en-el-Trabajo/DecretoSupremo005_2012_TR

_ ReglamentodelaLey29783_LeydeSeguridadySaludenelTrabajo.pdf.

8. Ministerio de Trabajo y

Promoción del Empleo. Política y Plan Nacional de Seguridad y Salud en el

Trabajo 2017 - 2021 [Internet]. Lima: MTPE; 2018. [citado

el 20/08/2019] Disponible en: https://www.trabajo.gob.pe/archivos/file/CNSST/politica_nacional_SST_2017_2021.pdf.

9. Merino-Salazar P, Cornelio

C, Lopez-Ruiz M, Benavides FG. Propuesta de

indicadores para la vigilancia de la salud ocupacional en América Latina y el

Caribe. Rev Panam Salud

Pública. 2018;42:1–9 [citado el 6 mayo 2019]. Disponible

en: https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.125.

10. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Encuesta Nacional de Programas Presupuestales

2011-2016 [Internet]. Lima: INEI; 2017 [citado el 31 enero 2020]. Disponible

en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1442/libro.pdf.

11. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Características de la Población Económicamente

Activa Ocupada [Internet]. Lima: INEI; 2012 [citado el 20/08/2019]. Disponible

en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1105/cap02.pdf.

12. Benavides FG,

Merino-Salazar P, Cornelio C, Assunção AA,

Agudelo-Suárez AA, Amable M, et al. Cuestionario básico y criterios

metodológicos para las Encuestas sobre Condiciones de Trabajo, Empleo y Salud

en América Latina y el Caribe. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32(9):e00210715 [citado el 14 mayo 2019]. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00210715.

13. Benavides F, Zimmermann M, Campos J, Carmenate

L, Baez I, Nogareda C, et

al. Conjunto mínimo básico de ítems para el diseño de cuestionarios sobre

condiciones de trabajo y salud. Arch Prev Riesgos Labor. 2010;13(1):13-22.

14. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Clasificacion Industrial

Internacional Uniforme de todas las actividaes economicas CIIU Revisión 4 [Internet]. Lima: INEI; 2010. [citado el 10 mayo 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib0883/Libro.pdf.

15. Sabastizagal

I, Vives A, Astete J, Burgos M, Gimeno Ruiz de Porras

D, et al. Fiabilidad y cumplimiento de las preguntas sobre condiciones de

trabajo incluidas en el cuestionario CTESLAC: resultados del Estudio sobre

Condiciones de trabajo, Seguridad y Salud en Perú. Arch

Prev Riesgos Labor. 2018;21(4):196-202

[citado el 14 agosto 2019]. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.12961/aprl.2018.21.04.3.

16. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Glosario de términos [Internet]. En: Compendio estadistico Perú 2016. Lima: INEI; 2016 [citado el

20/08/2019]. Disponible en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1375/glosario2.pdf

17. Instituto Nacional de

Estadística e Informática. Aspectos metodológicos [Internet]. Lima: INEI; 2012.

[citado el 05/11/2019]. Disponible en: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1106/cap01.pdf.

18. Ministerio de la

Protección Social. Primera Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Salud y Trabajo

en el Sistema General de Riesgos Profesionales [Internet]. Bogotá: Ministerio

de Protección Social; 2007. Disponible en: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Documentos%20y%20Publicaciones/ENCUESTA%20SALUD%20RP.pdf.

19. Ministerio de Trabajo,

Empleo y Seguridad Social. Primera Encuesta Nacional a Trabajadores sobre

Empleo, Trabajo, Condiciones y Medio Ambiente Laboral [Internet]. Buenos Aires:

MTEySS; 2009 [citado el 10 mayo 2019]. Disponible en:

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/primera_encuesta_nacional_trabajadores.pdf.

20. Ministerio de Salud,

Instituto de Seguridad Laboral y la Dirección del Trabajo. Primera Encuesta

Nacional de Condiciones de Empleo, Trabajo, Salud y Calidad de Vida de los

Trabajadores (ENETS 2009-2011) [Internet]. Santiago: MINSAL; 2009 [citado el 8

mayo 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.dt.gob.cl/portal/1629/articles-99630_recurso_1.pdf.

21. Benavides FG, Wesseling I, Delclós G, Felknor S, Pinilla J, Rodrigo F, et al. I Encuesta

Centroamericana sobre Condiciones de Trabajo y Salud (I ECCTS). [Internet].

Organización Iberoamericana de Seguridad Social (OISS); 2012 [citado el 19 mayo

2019]. Disponible en: http://www.oiss.org/estrategia/encuestas/lib/iecct/ESTUDIO_CUANTITATIVO_ECCTSSALTRA9.pdf.

22. Ministerio de Trabajo y

Promoción del Empleo. Anuario estadístico sectorial 2017. [Internet]. Lima:

MTPE; 2018. [citado el 20/09/2019] Disponible en: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/229919/Anuario_2017_opt.pdf.

23. Merino-Salazar P, Artazcoz L, Cornelio C, Iñiguez MJI, Rojas M,

Martínez-Iñigo D, et al. Work and health

in Latin America: results from the

working conditions surveys of Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Central America and Uruguay. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(6):432-9. [citado el 2

setiembre 2019]. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-103899.

24. EsSalud.

Presentación de los principales Resultados de la encuesta nacional

socioeconómica y de acceso a la salud de los asegurados de EsSalud

2015 [Internet]. Lima: EsSalud; 2016. [citado el 14 octubre 2019]. Disponible en: http://www.essalud.gob.pe/downloads/encuesta_nacional_socioeconomica/.

25. Eurofound.

Sixth European Working Conditions Survey–Overview report (2017 update) [Internet]. Luxembourg: Publications Office

of the European Union; 2017 [citado el 14 octubre 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1634en.pdf.

Funding:

Resources from the National Institute of Health of

Peru.

Citation: Sabastizagal-Vela I,

Astete-Cornejo J, Benavides FG. Working, safety and health conditions in the

economically active and employed population in urban areas of Peru. Rev Peru

Med Exp Salud Publica. 2020;37(1):32-41.

Doi:

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4592

Correspondence to:

Iselle Lynn Sabastizagal Vela; Centro Nacional de Salud

Ocupacional y Protección del Medio Ambiente para la Salud, Instituto Nacional

de Salud;

isabastizagal@ins.gob.pe.

Authors’ contributions: SIL and JMAC participated in the conception and design of the

article, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the

article, and approval of the final version. FGB, in technical advice, data

analysis and interpretation, critical review of the article and approval of the

final version.

Conflicts of interest:

This study does not represent any conflict of interest with the

authors or the institution.

Received:

06/06/2019

Approved:

19/02/2020

Online:

23/03/2020