10.17843/rpmesp.2020.372.4772

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Neonatal meningitis:

a multicenter study in Lima, Peru

Daniel Guillén-Pinto

1,2, Pediatric neurologist

1,2, Pediatric neurologist

Bárbara Málaga-Espinoza

1, physician

1, physician

Joselyn Ye-Tay  1, physician

1, physician

María Luz Rospigliosi-López

1,2, neonatologist

1,2, neonatologist

Andrea Montenegro-Rivera

1, pediatrician

1, pediatrician

María Rivas

4, Pediatric neurologist

4, Pediatric neurologist

María Luisa Stiglich

4, Pediatric neurologist

4, Pediatric neurologist

Sonia Villasante-Valera

4, neonatologist

4, neonatologist

Olga Lizama-Olaya

7, neonatologist

7, neonatologist

Alfredo Tori  7, Pediatric neurologist

7, Pediatric neurologist

Lizet Cuba

5, physician

5, physician

Luis Florián  5, neonatologist

5, neonatologist

Leidi Vilchez-Fernández

6, neurologist

6, neurologist

Oscar Eguiluz-Loaiza

6, neonatologist

6, neonatologist

Carmen Rosa Dávila-Aliaga

3, neonatologist

3, neonatologist

Pilar Medina-Alva

1,3, Pediatric neurologist

1,3, Pediatric neurologist

1 Universidad

Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Perú.

2 Hospital Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Perú.

3

Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal, Lima, Perú.

4 Hospital

Nacional Docente Madre Niño San Bartolomé, Lima, Perú.

5

Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, Lima, Perú.

6 Hospital

Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrión, Lima, Perú.

7 Hospital

Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen, Lima, Perú.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To

determine the incidence and the clinical, bacteriological and cerebrospinal

fluid characteristics of neonatal meningitis in Lima hospitals.

Materials and methods:

An observational, multicenter study was conducted in six hospitals in the city

of Lima during 1 year of epidemiological surveillance.

Results: The cumulative

hospital incidence was 1.4 cases per 1000 live births. A total of 53 cases of

neonatal meningitis were included, 34% (18/53) were early and 66% (35/53) late.

The associated maternal factors were meconium-stained amniotic fluid and urinary

tract infection. Insufficient prenatal check-ups were found in 58.8% (30/51).

The most associated neonatal factor was sepsis. The main symptoms were fever,

irritability, hypoactivity and respiratory distress. Pleocytosis in

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was significant, without predominance of

polymorphonuclear lymphocytes (PMN), hypoglycorrhagia and proteinorrhagia. The

most frequent pathogens isolated were Escherichia coli and Listeria

monocytogenes.

Conclusions: The

hospital incidence of neonatal meningitis was 1.4 per 1000 live births, being

ten times higher in preterm infants. Breathing difficulty was the most frequent

symptom in the early stage, while fever and irritability in the late stage. CSF

showed pleocytosis without predominance of PMN. The most frequent germs were

Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Ventriculitis and

hydrocephalus were the most common neurological complications.

Keywords:

Meningitis; Newborn; Premature; Cerebrospinal Fluid; Peru (source: MeSH

NLM).

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal

meningitis (NM) is a devastating disease, known to exist for over a century.

Early publications emphasized its clinical rarity and cumbersome diagnostic

process (1,2). However, over time it has

been reported on every continent, and despite scientific and technological

advances, it remains a public health problem (3).

Incidence

of NM varies considerably. In developed countries, it is estimated to be around

0.3 cases per 1,000 live births, while in developing countries this incidence

can be as high as 6.1 cases per 1,000 live births (3). With the new

methods, detection has improved and lethality has decreased; however, morbidity

remains high (20-60%) (4).

In

Peru, Oliveros reported 0.47 cases per 1,000 live births in 1993 (6).

However, in recent years an upward trend has been observed, ranging from 0.9 to

1.5 cases per 1,000 live births (5-7). This incidence could be

greater in our population due to the high frequency of maternal-perinatal

factors, such as insufficient prenatal control, sepsis, immaturity due to

prematurity and factors inherent to neonatal intensive care (5).

NM is

classified in 2 types, early and late (8). Early NM starts within

the first 72 hours and is related to contamination through the birth canal with

bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Streptococcus group B and Listeria

monocytogenes (9,10). After 72 hours,

late NM is associated with germs from the hospital environment, such as

coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and gram-negative bacilli (Escherichia

coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter

spp.) (9-11).

NM is

a health emergency, and as soon as it is suspected, empirical antibiotic

treatment should be indicated (12). However, diagnosis is complex

due to the low specificity of signs and symptoms and the difficulty of

isolating the germs by culture. So, when risk factors are detected, clinical

suspicion is the only alternative (2,8).

Given

the scarce information on NM in our country regarding aspects such as its

frequency, impact on morbimortality and the prevalence of the pathogens

involved (9,12), it is extremely important to know the

epidemiological and clinical profile of the disease. For this reason, the

objective of the study was to estimate the incidence, associated factors,

clinical aspects and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) characteristics, etiology, and

complications of NM in hospitals in the city of Lima.

|

KEY

MESSAGES

|

|

Motivation

for the study:

The frequency of neonatal meningitis in some

hospitals and the absence of a treatment protocol motivated an

epidemiological surveillance study in Lima.

Main

findings: An incidence of 1.4 cases per 1,000 live births was found, preterm infants represented the highest proportion.

Symptoms were non-specific, mainly respiratory distress in early NM, and

fever and irritability in the late type. Cerebrospinal fluid showed moderate pleocytosis with hypoglycorrhachia

and hyperproteinorrhachia. Escherichia coli

and Listeria monocytogenes predominated.

Implications: There is a need

to standardize the diagnostic and treatment criteria for NM. Likewise,

epidemiological surveillance should continue in the neonatal units of our

country.

|

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and population

Multi-center

case series study carried out between 2017 and 2018, with the aim of carrying

out hospital epidemiological surveillance of NM for 12 consecutive months in

Lima hospitals, without intervening in the diagnosis and treatment processes.

To be

included in the study, hospitals had to have neonatal units, neonatal

physicians, specialized nursing staff, specialists in neurology or neuropediatrics, neuroimaging equipment and a clinical

laboratory suitable for processing general analysis and cytochemical and

bacteriological examination of CSF. For this purpose, 12 hospitals were

selected, from which 6 met the inclusion criteria: Hospital Cayetano Heredia

(HCH), Hospital Nacional Docente Madre Niño San Bartolomé

(HSB), Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza (HNAL), Instituto Nacional

Materno Perinatal (INMP), Hospital Nacional Guillermo

Almenara Irigoyen (HNGAI) and Hospital Nacional

Daniel Alcides Carrión

(HNDAC). All were level III health facilities.

A

research team was organized with physicians representing each of the six

hospitals, who were trained in the process of inclusion, follow-up and

collection of clinical and laboratory data. All centers had a neonatologist and

a neurologist. A new-case alert system was developed. The possibility of a

case, was recorded, communicated and confirmed by the representant of each

hospital. The monitoring and data collection continued until discharge. An ad

hoc clinical file was created, with data about filiation, sex, age,

gestational age, prenatal, birth and postnatal data, CSF characteristics and

bacteriological data. There was no interference in management decisions. In all

hospitals the objectives of the project were presented to the pediatric medical

team.

In

order to estimate hospital incidents, the number of births during the

observation period was recorded, according to the perinatal register and

statistics office of each hospital. Finally, premature births were recorded by

gestational age and sex.

Variables

All full-term

infants under 28 days or pre-term infants under 44 weeks corrected gestational age

were entered into the study. The inclusion criteria for all cases of NM were

infants who were symptomatic or at risk of infection; pleocytosis

≥ 30 leukocytes/μL in CSF, diagnosis and care at the

hospital of birth. The hospital follow-up concluded with the discharge of the

patient. Neonates with severe cerebral malformations and spinal dysraphism were

excluded.

NM categorization

was confirmed (germ identified), probable (high bacterial suspicion), and

possible (low bacterial suspicion) (5,11).

NM was confirmed when the germ was identified in the CSF, by culture,

polymerase chain reaction (PCR), coagglutination or

blood culture. Probable NM was defined by hypoglycorrhachia (glycorrhachia ≤50%

of serum glucose or absolute glycorrhachia of ≤40 mg/dL) and hyperproteinuria

(proteinuria ≥60 mg/dL) (5,8). Cases of possible NM had any level of glycorrhachia or proteinorrhachia

or normal biochemical values. The viruses were identified by PCR or viral indirect

immunofluorescence (viral IIF) in the CSF. The fungi were identified by CSF

culture/PCR. In the case of lumbar punctures (LP), a leukocyte was discounted

for every 500 red blood cells in CSF.

Early

MN was defined as, confirmed, probable or possible cases diagnosed before 72

hours of age. Late NM was defined as cases diagnosed after 72 hours of

age (5,8). Early neurological

complications were defined within the first seven days of detection. The

complications considered were hydrocephalus, ventriculitis, subdural effusion

and cerebral infarction, identified by cerebral ultrasound or cerebral magnetic

resonance.

In

order to measure the burden of disease, out-of-hospital cases were recorded.

Out-of-hospital cases are defined as cases of NM born in other hospitals and

admitted during the study period.

A set

of prenatal, natal and postnatal variables were recorded and analyzed. Numerical

variables were: maternal age, antenatal control, gestational age, birth weight;

and categorical variables were: maternal urinary infection, maternal fever,

chorioamnionitis, presence of meconium amniotic fluid, pre-eclampsia /

eclampsia, asphyxia, intraventricular hemorrhage, sepsis, anemia, meconium

aspiration, fever, respiratory distress, hypoactivity, irritability, vomiting.

Likewise, CSF characteristics and germ frequencies, treatment, complications

and lethality were recorded and analyzed.

Ethical considerations

The

identity of the patients was protected by numerical codes. The project was also

approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Universidad Peruana Cayetano

Heredia and by the ethics committees of each of the participating hospitals.

Statistical Analysis

The

information was collected and stored in a Microsoft Excel 2016 © database.

The accumulated incidence during one year of observation in each hospital was

determined. The project started in several successive months in 2017 and ended

sequentially in 2018. The cumulative incidence was estimated from the sum of

confirmed cases, probable cases and possible cases divided by the number of

live births. Out-of-hospital cases were not considered for the incidence

calculation.

The

frequencies of clinical and laboratorial variables are presented for early,

late and out-of-hospital NM. Numerical variables were summarized with medians

and their interquartile range. Logistic regression was performed to determine

the influence of some factors on early meningitis with respect to late

meningitis, by analyzing all cases. Homogeneity was determined by the Levene and Forsythe-Browne tests. The only few missing data

were from the prenatal control variable, so no replacement technique was

necessary.

RESULTS

Patient Enrollment

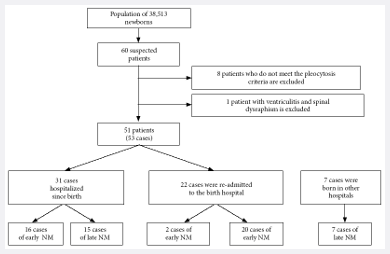

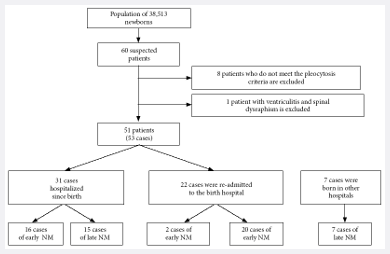

The

project started in 2017. Given that the enrollment in hospitals was carried out

gradually, the study was completed in 2018. During this period a total of

38,513 live neonates were registered in the six hospitals, of which 51 patients

were included who developed 53 cases of NM, one patient presented three

episodes of NM. From the reported cases, 41.5% (22/53) were neonates who,

having left the hospital in good condition, were readmitted on suspicion of an

infectious process. During the study period, seven out-of-hospital cases were

admitted (Figure

1), considered only for the profile of clinical, etiological

and laboratorial analysis.

NM: neonatal meningitis

Figure 1. Patient

flow chart.

The

average maternal age was 27.2 years and parity was 2.3 per woman. The number of

prenatal controls was also insufficient in 58.8% (30/51) of the mothers. From

the neonates, 54.7% (29/53) were born prematurely before 37 weeks. The

population studied was homogeneous among the hospitals included.

Epidemiological

characteristics

The

hospital incidence was 1.4 cases per 1,000 live births, with a wide variation

among hospitals, from 0 to 3.2 cases per 1,000 live births. HCH and HNDMNSB had

the highest incidence. In pre-term infants under 37 weeks, the NM incidence was

7.5 cases per 1,000 live births and 0.7 cases per 1,000 live full-term births

(Table 1).

Table 1. Cumulative incidence of neonatal meningitis according

to hospital institution

|

Institution |

Total |

Pre-term |

|

Live births |

Cases |

Cumulative incidence (per 1,000 live births) |

Live births |

Cases |

Cumulative incidence (per 1,000 live births) |

|

Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia |

4,436 |

14 |

3.2 |

826 |

7 |

8.5 |

|

Hospital Nacional Docente Madre

Niño San Bartolomé |

6,155 |

20 |

3.2 |

395 |

8 |

20.3 |

|

Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal |

18,138 |

17 |

0.9 |

1,634 |

13 |

8.0 |

|

Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza |

2,765 |

1 |

0.4 |

226 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Hospital Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrión |

3,915 |

1 |

0.3 |

481 |

1 |

2.1 |

|

Hospital Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen |

3,104 |

0 |

0.0 |

280 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Total |

38,513 |

53 |

1.4 |

3,842 |

29 |

7.5 |

Surveillance during a 1-year period.

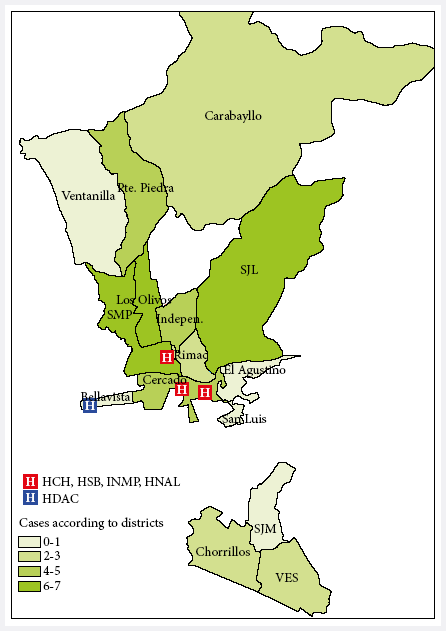

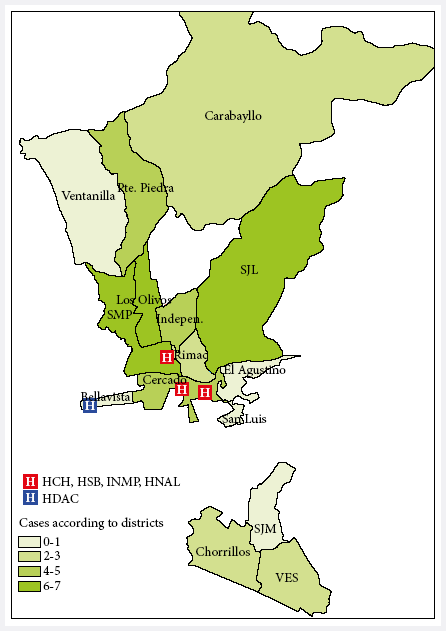

The male/female ratio was 1.4; males represented the 58.3% (35/60) and

females 41.7% (25/60). The majority of patients were from northern Lima at 42%

(25/60), mainly from the districts of San Martín de Porres

and Los Olivos, followed by districts of eastern Lima

at 15% (9/60).

Figure 2 shows that the cases came from areas surrounding the

hospitals.

HCH: Hospital Cayetano Heredia

HSB: Hospital San Bartolomé

HNAL: Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza

HDAC: Hospital Daniel Alcides Carrión

INMP: Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal

Figure 2.

Distribution of neonatal meningitis cases by district of origin (Metropolitan

Lima)

From the total, 34% (18/53) were early NM cases and 66% (35/53) were late

NM cases. Cases of confirmed NM were 58.5% (31/53), of which 25.8% (8/31) were

early and 74.2% (23/31) late. Bacterial NM occurred in 87.1% (27/31) of the

confirmed cases and viral NM in 12.9% (4/31). Probable NM was 22.6% (12/53) of

the total of cases and possible NM was 18.9% (10/53). Regarding outpatients, 4

had confirmed NM, 2 had probable NM and 1 had possible NM.

Clinical

characteristics

For early NM, the associated prenatal factors were meconial amniotic

fluid (38.9%), urinary tract infection (33.3%), maternal fever (27.8) and

chorioamnionitis (22.2%). However, in the late NM, these factors did not seem

to have a major influence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prenatal, natal and postnatal characteristics, according to the type of

meningitis

|

Characteristic |

Early NM (n = 18) |

Late NM (n = 35) |

Out-of-hospital NM (n = 7) |

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

Cesarean section delivery |

11 (61.1) |

18 (51.4) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Prenatal controls |

|

|

|

|

<6 |

10 (55.5) |

17 (54.8) |

3 (42.9) |

|

6 or more |

4 (22.3) |

14 (45.2) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Prenatal and natal factors |

|

|

|

|

Medications during pregnancy |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Maternal fever |

5 (27.8) |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Premature rupture of membranes >18 h |

3 (16.7) |

9 (25.7) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Urinary tract infection |

6 (33.3) |

7 (20.0) |

2 (28.6) |

|

Vaginal infection |

0 (0.0) |

2 (5.7) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Pelvic-uterine surgery |

1 (5.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid |

7 (38.9) |

9 (25.7) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Chorioamnionitis |

4 (22.2) |

5 (14.3) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Prolonged labor |

2 (11.1) |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Preeclampsia/eclampsia |

2 (11.1) |

5 (14.3) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Intrauterine growth restriction |

0 (0.0) |

2 (5.7) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Male gender |

11 (61.1) |

20 (57.1) |

4 (57.1) |

|

Gestational age (weeks) |

|

|

|

|

<37 |

11 (61.1) |

18 (51.4) |

3 (42.9) |

|

≥37 |

7 (38.9) |

17 (48.6) |

4 (57.1) |

|

Weight (grams) |

|

|

|

|

<1,500 |

4 (22.2) |

9 (25.7) |

2 (28.6) |

|

1,500 to 2,499 |

7 (38.9) |

10 (28.6) |

1 (14.3) |

|

≥2,500 |

7 (38.9) |

16 (45.7) |

4 (57.1) |

|

Age at the onset of symptoms (days)

a |

0.9 (1.8) |

18.6 (20.1) |

11.9 (11.6) |

|

Postnatal factors |

|

|

|

|

Sepsis |

9 (50.0) |

7 (20.0) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Asphyxia |

1 (5.6) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (28.6) |

|

Meconium aspiration |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Intraventricular hemorrhage |

4 (22.2) |

2 (5.7) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Anemia |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Connatal pneumonia |

1 (5.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Pathological jaundice |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Symptoms |

|

|

|

|

Fever |

7 (38.9) |

19 (54.3) |

5 (71.4) |

|

Irritability |

7 (38.9) |

20 (57.1) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Hypoactivity |

7 (38.9) |

17 (48.6) |

4 (57.1) |

|

Breathing difficulty |

13 (72.2) |

10 (28.6) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Weak sucking |

4 (22.2) |

12 (34.3) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Vomiting |

1 (5.6) |

2 (5.7) |

4 (57.1) |

|

Jaundice |

4 (22.2) |

4 (11.4) |

5 (71.4) |

|

Apnea |

5 (27.8) |

7 (20.0) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Convulsions |

2 (11.1) |

6 (17.1) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Bulging fontanelle |

3 (16.7) |

2 (5.7) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Hypotonia |

5 (27.8) |

6 (17.1) |

3 (42.9) |

|

Hypertonia |

3 (16.7) |

2 (5.7) |

2 (28.6) |

|

Hyperreflexia |

1 (5.6) |

3 (8.6) |

1 (14.3) |

|

Hyporreflexia |

2 (11.1) |

1 (2.9) |

2 (28.6) |

|

Lethality |

1 (5.6) |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0.0) |

NM: neonatal meningitis

a Mean (SD)

Sepsis was the most important factor related to NM; and according to the

NM types, 50% (9/18) were early meningitis cases, 20% (7/35) were late

meningitis cases and 42.9% (3/7) were of out-of-hospital meningitis cases. The average

age for the onset of symptoms in early NM cases was 0.9 days; 18.6 days in late

NM; and 11.9 days in the out-of-hospital cases. Symptoms such as respiratory distress, were more common in the early NM. In late NM,

fever, irritability and hypoactivity predominated (Table 2). Table 5 shows the

risk factors associated with early NM in relation to late NM.

Table 5. Factors associated with early neonatal meningitis compared to late

neonatal meningitis.

|

Factor |

OR |

p-value |

95% CI |

|

Maternal fever |

18.51 |

0.021 |

1.56-219.87 |

|

Sepsis |

5.10 |

0.040 |

1.08-24.07 |

|

Breathing difficulty |

4.59 |

0.043 |

1.05-20.11 |

|

Cesarean section delivery |

4.12 |

0.079 |

0.85-20.01 |

OR: Odds Ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Cytochemical and bacteriological

characteristics of the CSF

On average, 2.5 and 2 LPs were performed for early and late NM,

respectively. In most cases of early NM, the LP was performed on the first day

of hospitalization; and in cases of late NM, it could take until the third day

of illness.

In

Table 3, the cytochemical characteristics of the CSF are presented.

The median value for pleocytosis was 225 leukocytes/μL for early NM

and 202 leukocytes/μL for late NM, the median value

for polymorphonuclears (PMN) was of 57% and 30%, respectively. Hypoglycorrhachia

was similar in both types of meningitis and hyperproteinorrhachia

was higher in early NM. In the out-of-hospital type, there was less pleocytosis and more glycorrhachia

(

Table 3).

Table 3.

Cerebrospinal fluid characteristics, according to the

type of meningitis.

|

Variable |

Early NM (n = 18) |

Late NM (n = 35) |

Out-of-hospital NM (n = 7) |

|

Median |

IQR |

Median |

IQR |

Median |

IQR |

|

Leucocytes (cells/μL) |

225 |

130-1912 |

202 |

45-530 |

150 |

32-866 |

|

PMN (%) |

57 |

30-70 |

30 |

10-52 |

60 |

35-60 |

|

Glucose (mg/dL) |

36 |

24-42 |

32 |

25-44 |

43 |

34-46 |

|

Proteins (mg/dL) |

188 |

115-499 |

125 |

81-201 |

139 |

62-266 |

|

Erythrocytes (cells/μL) |

100 |

10-500 |

3 |

0-100 |

32 |

5-50 |

NM: neonatal meningitis, IQR: interquartile range (25th and 75th

percentiles), PMN: polymorphonuclears

A total of 35 germs were identified, including bacteria, viruses

and a case of Candida albicans. In all clinical types, Escherichia

coli and Listeria monocytogenes predominated. In 17.1% (6/35) of the

cases the germ was isolated both in blood culture and in the CSF. Escherichia

coli was found in four of those cases, group B Streptococcus

and coagulase negative Staphylococcus, in one case each. Cases of

influenza B, coronavirus and adenovirus were identified by indirect

immunofluorescence (IIF). In a single case, PCR was performed, isolating herpes

virus VI (Table 4).

Table 4.

Isolation of the infectious agent according to the

type of meningitis.

|

Infectious agent |

Cultivated

fluid |

Early

NM |

Late

NM |

Out-of-hospital

NM |

Total |

|

Escherichia coli |

CSF |

3/18 |

2/35 |

0/7 |

10/60

a |

|

Blood |

2/18 |

7/35 |

0/7 |

|

Listeria monocytogenes |

CSF |

1/18 |

2/35 |

0/7 |

8/60 |

|

Blood |

3/18 |

2/35 |

0/7 |

|

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

1/7 |

3/60

a |

|

Blood |

1/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

|

Group B Streptococcus |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

1/7 |

2/60

a |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

0/35 |

1/7 |

|

Enterococo faecium |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

2/60 |

|

Blood |

1/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

|

Staphilococus epidermidis |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

2/60 |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

2/35 |

0/7 |

|

Serratia marcescens |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

|

Serratia liquecies |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

1/35 |

077 |

|

Staphilococus hominis |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

0/35 |

1/7 |

|

Influenza B (IIF) |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Adenovirus (IIF) |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Coronavirus (IIF) |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Herpes virus VI (PCR) |

CSF |

0/18 |

1/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Candida albicans

(PCR) |

CSF |

0/18 |

0/35 |

0/7 |

1/60 |

|

Blood |

0/18 |

0/35 |

1/7 |

NM: neonatal meningitis; CSF:

cerebrospinal fluid; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; IIF: indirect

immunofluorescence

a

Isolation of the germ in both blood

and CSF

The total

represents the burden of disease addressed by all the hospitals.

Treatment

and special conditions

Treatment schedules were highly variable. The mean duration for cases of

early NM was 21 days and 19.5 days for late meningitis. Before the

first LP was performed, 62% of children received antibiotics. The most commonly

used drugs were ampicillin (60%), cefotaxime (38%), vancomycin (28%), meropenem

(33%) and gentamicin (22%), in different schedules.

In the specific analysis of late meningitis, not including outpatients,

two groups were differentiated (Figure 1). In the first group, 86.7% (13/15) of

patients were pre-term infants, 46.6% (7/15) had respiratory distress, most

were diagnosed at seven days of age, and their CSF was characterized by

increased pleocytosis. In the second group, 75% (15/20) were full-term infants,

fever and irritability were the most frequent symptoms and the diagnosis was

made within the first two days of hospitalization.

Three patients had special presentations. One had minor pleocytosis and

urinary-related bacteremia by Escherichia coli; another had normal

initial cytochemistry, but with a CSF culture positive for Escherichia coli

that later developed pleocytosis; and the third one had three episodes of

meningitis (recurrent) by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia

coli.

Complications

and lethality

At least one neurological complication was observed in 25% (15/60) of

the cases, from which, 73.3% (11/15) were pre-term infants. Early and late

neurological complications were ventriculitis and hydrocephalus respectively.

From the cases with late NM, 95.2% (40/42) were discharged with

favorable evolution, early NM had a favorable

evolution in 77.8% (14/18) of the cases. Four cases were referred to a hospital

with a higher complexity level. Two neonates died (3.3%), one presenting early

NM and the other, the late type.

DISCUSSION

NM had a hospital incidence of 1.4 cases per 1,000 live births, with a

higher risk in pre-term than in full-term infants. The wide variability in

incidence leads to the suspicion that diagnostic protocols for NM were not standarized across hospitals. A variety of causal germs,

mostly bacteria, were identified, with the frequency of Eschericha

coli and Listeria monocytogenes being particularly noteworthy.

We present a larger NM clinical scenario than those known. In this

scenario the early type is related to birth conditions and the late type is related

to prolonged stay of pre-term infants in neonatal units (9). We

provide a new viewpoint, derived from the community, which occurs more in

full-term infants near the second week, related to a higher proportion of viral

agents.

Neonatal meningitis is an under-diagnosed and under-recorded prevalent

disease in our country (5,13). In 2016, Zea et al., noted that LP is often deferred

in confirmed sepsis (14). Likewise, in a similar population it has

been observed that medical criteria may vary depending on the level of medical

specialization (15).

We present an epidemiological surveillance study according the

management protocols of each hospital. The incidence of 1.4 per 1,000 live

births is an average value worldwide (3), and is initially taken as a

reference. This value will have to be adjusted in the future when the

diagnostic criteria are standardized. However, the high incidence in premature

infants alerts us about the need for vigilance in neonatal units (2, 16).

This study was characterized by the inclusion of cases with defined pleocytosis. This was made to meet the inflammatory criteria for meningitis, classified

as confirmed, probable and possible, according to the definition of neonatal

sepsis. Therefore, more positive isolates were found in blood cultures. Less were found to be positive in blood and CSF cultures, and

only a few cases were observed solely in CSF culture. We believe that PCR could have helped to reduce

the number of probable and possible cases, and to identify cases of pleocytosis

as just an inflammatory phenomenon (8,9,17).

All known risk factors for neonatal sepsis are related to NM (12,18). For the early type, peripartum fever and

incomplete prenatal controls were found to be risk factors. These factors

suggest the risk of microbial invasion from the vaginal flora, the subsequent

placental inflammatory response, initiation of labor and consequently sepsis

and meningitis (8). However, other clinical and sociocultural

factors may not be considered.

Classically, NM is divided into early and late according to its

mechanism of contamination (12,16,19).

However, we have identified a third group of patients who come from their

homes, from the community environment, are term infants, febrile and irritable

with less pleocytosis, contaminated with common respiratory tract agents, both

bacterial and viral, and in some cases by germs that colonize maternal

secretions.

The age of symptoms onset for both types of NM was found to be within

the expected ranges, 0.9 days for early NM cases and 18.6 days for late NM

cases. This was found to be in accordance with other series, and clearly

associated with the type of birth and neonatal unit stay (12,16,20). The group of children of out-of-hospital

origin also behaved as late NM at 11.9 days.

The symptoms were more frequent in early NM than in the late type, being

very nonspecific and related to sepsis. Among them, respiratory difficulty

stood out in 70% of early cases, perhaps due to lung immaturity in the

premature group or to respiratory acidosis (3,12,16).

In late NM more neurological symptoms were observed (1,3).

However, identification of these symptoms depends on the experience of the

examiner (14,21). Maternal fever, sepsis,

and respiratory distress were three factors found to be more likely to develop

in early NM than in the late type. These were probably generated by maternal

infections, urinary tract infections and chorioamnionitis (1,8). It will remain for future studies to ensure the

diagnosis of chorioamnionitis by pathological examination of the placenta.

In most cases, more than one LP was carried out, following international

guidelines. Given that NM is a difficult to diagnose multi-symptomatic disease

caused by many aggressive agents, the guidelines recommend that the LP be

performed prior to the use of antibiotics. It is also recommended that a new control

should be performed within 48-72 hours, especially if there is no clinical

improvement, with the purpose of reducing the bacterial load or achieving sterilization

of the CSF (14,21,22).

In both clinical types, moderate pleocytosis without PMN predominance

was noted, they also presented hypoglycorrhachia and proteinorrhachia. This particular characteristic has

already been observed in other national studies (6,7),

perhaps, bacteriological factors, sample processing and patient’s immunological

conditions are involved. In bacterial NM, hypoglycorrhachia

and proteinorrhachia are common findings. These are explained

by glucose consumption and increased detritus, their persistence for more than

two weeks has been associated with poor prognosis (23). However,

these indicators may be aggravated by the presence of intracranial hemorrhage.

Also, on rare occasions, the first LP may not demonstrate pleocytosis, and a

second sample may be required within 12 to 24 hours (21).

The microbiological behavior of NM has varied regarding time and

different geographical areas (2,3,16,24-26).

Streptococcus agalactie stands out mainly in

developed countries and gram‑negative bacteria in non‑developed countries (3,24). In this series, Eschericha

coli and Listeria monocytogenes were the prevalent germs in both types

of NM, followed by a variety of gram‑negative and gram‑positive bacteria, fewer

virus cases and one case of Candida albicans, all described in different

case series.

NM by Eschericha coli has been

known for many decades (1,2) to be a part

of early neonatal sepsis cases. It can also cause late NM, usually associated

with severe acute and mid‑term complications such as hydrocephalus, subdural

effusions, cerebral infarctions and abscesses (2,27).

In recent years, the increased frequency of beta‑lactamase strains and their

antimicrobial resistance has being notable (24,26).

Therefore, their presence in this series alerts about early identification and

treatment.

Listeria monocytogenes is a pathogen that has become

more important in Peruvian series in recent years (5,7).

It has been observed to be 5-20% (26) of the early and late types

reported, and it usually produces a moderate or severe disease, according to

some international and national reports. However, its infectious mechanism is

not clearly identified, but it is understood that the invasion is by

genitourinary route and related to the maternal intestinal flora.

The lethality rate by NM in national reports has been decreasing over

time. In 1993, Oliveros et al. reported 20% death in a series

of 24 cases (6), and in 2017, Lewis reported 3.8% in a series of 53

patients (5). Such decrease may be related to early diagnosis and

treatment. However, the frequency of neurological complications was 25%, and

the high morbidity in premature infants (75%) was noteworthy (28,29). Consequently, the use of cerebral ultrasound as

a diagnostic tool for hydrocephalus, ventriculitis and cerebral infarction is

very important in premature infants (30).

Not including certain variables such as prenatal steroid use,

intrauterine infections, histological chorioamnionitis, invasive procedures,

recording of sepsis cases without meningitis, antimicrobial sensitivity and

resistance, community contacts, and not involving more hospitals are among the

main limitations of this study. However, the strengths of the study were to

demonstrate that NM is frequent, that pre-term infants are at greater risk,

that the disease can present itself in different ways and that a wide spectrum

of causal infectious agents exists. With these considerations we contribute to

the national knowledge of this disease.

In conclusion, the hospital incidence of NM was 1.4 cases per 1,000 live

births, and even higher in premature infants. Respiratory distress was the most

frequent symptom for early NM, while fever and irritability were the most

frequent symptoms of late NM. Moderate pleocytosis,

with hypoglycorrhachia and proteinorrhachia,

was noted in the CSF. The most frequent pathogens isolated were Eschericha coli and Listeria monocytogenes.

The most common neurological complications were ventriculitis and

hydrocephalus. A new pathogenic scenario for NM is proposed, it consists of

three infection types: vertical infection, by vaginal flora germs; nosocomial

infection, by contamination in neonatal units; and infection from the community

by common germs.

A national epidemiological surveillance study of NM is recommended. This

study should standardize diagnostic criteria (clinical, cytochemical, culture, PCR),

neuroimaging criteria (ultrasound and resonance) and criteria for

identification of perinatal risk factors.

Acknowledgement:

To all physicians and nurses in the neonatal departments of the

participating hospitals.

REFERENCES

1. Bell WE, McCormick

WF, Murillo PL. Meningitis neonatales. Infecciones neurológicas en el

niño. 2a ed. Barcelona: Salvat; 1979.

2. Ziai M, Haggerty RJ.

Neonatal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1958;259(7):314-20. doi:

10.1056/NEJM195808142590702.

3. Ku LC, Boggess KA,

Cohen-Wolkowiez M. Bacterial Meningitis in the Infant. Clin Perinatol.

2015;42(1):29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.10.004.

4. Holt DE. Neonatal

meningitis in England and Wales: 10 years on. Arch Dis Child - Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2001;84(2):85F-89.

5. Lewis G, Schweig M, Guillén-Pinto D, Rospigliosi ML.

Meningitis neonatal en un hospital general de Lima, Perú, 2008 al 2015. Rev

Peru Med Exp Salud Pública. 2017; 34:233-8. doi:

10.17843/rpmesp.2017.342.2297.

6. Oliveros Donohue MA,

Ramos Pianezzi R, León Cueto JL, Mazzini Pérez-Reyes J, Van Oordt,

Bellido J, Livia Becerra C. Meningitis neonatal en la UCI del Hospital

Edgardo Rebagliati Martins (IPSS) 1986-88. Diagnóstico.

1993;32(4/6):73-7.

7. Lazo E, Guillén D, Zegarra J. Meningitis neonatal

en el Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia. Rev Peru Pediatr.

2008;61(3):157-164.

8. Volpe J. Bacterial and Fungal Intracranial

Infections. Neurology of the Newborn. Fifth Edition. Philadelphia:

Saunders Elsevier; 2013.

9. Devi U, Bora R,

Malik V, Deori R, Gogoi B, Das JK, Mahanta J. Bacterial aetiology of

neonatal meningitis: A study from north-east India. Indian J Med Res.

2017 Jan;145(1):138-143. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_748_15.

10. Pérez RO, Lona JC,

Quiles M, Verdugo MÁ, 4Ascencio EP, Benítez EA. Sepsis neonatal temprana,

incidencia y factores de riesgo asociados en un hospital público del

occidente de México. Rev Chil Infectol. 2015;32(4):447-452.

11. Zea-Vera A, Turin CG, Ochoa TJ. Unificando los

criterios de sepsis neonatal tardía: propuesta de un algoritmo de

vigilancia diagnóstica. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública.

2014;31(2):358-63.

12. Perlman JM, Cilio M. Neonatal Meningitis: Current

Treatment Options. Neurology. Neonatology Questions and Controversies.

Third Edition. Phyladelphia: Elsevier; 2019.

13. Medina, María del Pilar. Frecuencia de enfermedad

neurológica en recién nacidos. Rev Peru Pediatr. 2007;60(1):11-9.

14. Zea-Vera A, Turín CG, Rueda MS, Guillén-Pinto D.

Uso de la punción lumbar en la evaluación de sepsis neonatal tardía en

recién nacidos de bajo peso. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública.

2016;33(2):278-282.

15. Vera S.

Variabilidad del criterio para indicar la punción lumbar en las unidades

de cuidados intensivos neonatales [tesis de bachiller]. Lima: Facultad

de Medicina, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; 2018.

16. Coto GD, López JB,

Fernández B, Fraga JM, Fernández JR, Reparaz R, et al. Meningitis

neonatal. Estudio epidemiológico del Grupo de Hospitales Castrillo. An

Pediatr. 2002;56(6):556-63.

17. Marcilla C, Martínez A, Carrascosa M, Baquero M,

Alfaro B. Meningitis víricas neonatales. Importancia de la reacción en

cadena de la polimerasa en su diagnóstico. Rev Neurol. 2018; 67:484-490.

18. Shane AL, Sánchez

PJ, Stoll BJ. Neonatal sepsis. Lancet. 2017;390(10104):1770-80. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31002-4.

19. Zhao Z, Yu J-L,

Zhang H-B, Li J-H, Li Z-K. Five-Year Multicenter Study of Clinical Tests

of Neonatal Purulent Meningitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila).

2018;57(4):389–97. doi: 10.1177/0009922817728699.

20. Olmedo I, Pallas

CR, Miralles M, Simón de las Heras R, Rodriguez J, Chasco A. Meningitis

neonatal: Estudio en 56 casos. An Esp Pediatr. 1997; 46:189-194.

21. Garges HP. Neonatal

Meningitis: What Is the Correlation Among Cerebrospinal Fluid Cultures,

Blood Cultures, and Cerebrospinal Fluid Parameters? Pediatrics.

2006;117(4):1094–100.

22. Greenberg RG, Benjamin DK, Cohen-Wolkowiez M,

Clark RH, Cotten CM, Laughon M, et al. Repeat lumbar punctures in

infants with meningitis in the neonatal intensive care unit. J

Perinatol. 2011;31(6):425–429. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.142.

23. Tan J, Kan J, Qiu G, Zhao D, Ren F, Luo Z, Zhang

Y. Clinical Prognosis in Neonatal Bacterial Meningitis: The Role of

Cerebrospinal Fluid Protein. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 28;10(10):e0141620. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0141620.

24. Collaborative Study

Group for Neonatal Bacterial Meningitis. A multicenter epidemiological

study of neonatal bacterial meningitis in parts of South China. Zhonghua

Er Ke Za Zhi Chin J Pediatr. 2018;56(6):421–428. doi:

10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2018.06.004.

25. Berardi A , Lugli L

, Rossi C , China MC , Vellani G , Contiero R , et al. Infezioni

da Streptococco B Della Regione Emilia Romagna . Neonatal bacterial

meningitis. Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62(3 Suppl 1):51-4.

26. Bentlin MR,

Ferreira GL, Rugolo LMS de S, Silva GHS, Mondelli AL, Rugolo Júnior A.

Neonatal meningitis according to the microbiological diagnosis: a decade

of experience in a tertiary center. Arq Neuropsiquiatr.

2010;68(6):882–887.

27. Zhu M-L, Mai J-Y, Zhu J-H, Lin Z-L. Clinical

analysis of 31 cases of neonatal purulent meningitis caused by

Escherichia coli. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi Chin J Contemp

Pediatr. 2012;14(12):910–912.

28. Ouchenir L, Renaud C, Khan S, Bitnun A, Boisvert

A-A, McDonald J, et al. The Epidemiology, Management, and

Outcomes of Bacterial Meningitis in Infants. Pediatrics.

2017;140(1):1-8. Pediatrics. 2017 Jul;140(1). doi:

10.1542/peds.2017-0476.

29. Krebs VLJ, Costa

GAM. Clinical outcome of neonatal bacterial meningitis according to

birth weight. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65(4b):1149–1153.

30. Gupta N, Grover H, Bansal I, Hooda K, Sapire JM,

Anand R, Kumar Y. Neonatal cranial sonography: ultrasound findings

in neonatal meningitis-a pictorial review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2017

Feb;7(1):123-131. doi: 10.21037/qims.2017.02.01.

Citation:

Guillén-Pinto D, Málaga-Espinoza B, Ye-Tay J, Rospigliosi-López ML,

Montenegro-Rivera A, Rivas M, et al.

Neonatal

meningitis: a multicenter study in Lima, Peru. Rev Peru

Med Exp Salud Publica. 2020;37(2):210-9. doi:

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.372.4772

Correspondence to:

Daniel Guillén Pinto; Av. Honorio Delgado

430, Urb. Ingeniería, San Martín de Porres, Lima, Perú;

dgu4illenpinto@gmail.com.

Funding:

This research was entirely self-financed.

Authors’ contributions:

DGP participated in the

conception of this study. DGP, BM and JY participated in the study design,

writing and data analysis. BM and JY participated in the enrollment and data

collection. MLR, AM, MR, MLS, SV, OL, AT, LC, LF, LV, OE, CD and PM

participated in the data collection. All authors reviewed and approved the

article.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no

conflict of interest.

Received: 30/08/2019

Approved:

29/04/2020

Online: 15/06/2020

![]() 1,2, Pediatric neurologist

1,2, Pediatric neurologist![]() 1, physician

1, physician![]() 1, physician

1, physician![]() 1,2, neonatologist

1,2, neonatologist![]() 1, pediatrician

1, pediatrician![]() 4, Pediatric neurologist

4, Pediatric neurologist![]() 4, Pediatric neurologist

4, Pediatric neurologist![]() 4, neonatologist

4, neonatologist![]() 7, neonatologist

7, neonatologist![]() 7, Pediatric neurologist

7, Pediatric neurologist![]() 5, physician

5, physician![]() 5, neonatologist

5, neonatologist![]() 6, neurologist

6, neurologist![]() 6, neonatologist

6, neonatologist![]() 3, neonatologist

3, neonatologist![]() 1,3, Pediatric neurologist

1,3, Pediatric neurologist