Eduardo Falconí-Rosadio

Joshi Acosta

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Interpretation systems, therapeutic itineraries and repertoires

of leprosy patients in a low prevalence country

Carmen Osorio-Mejía

![]() 1,

Microbiological biologist,

Public Health specialist

1,

Microbiological biologist,

Public Health specialist

Eduardo Falconí-Rosadio

![]() 1, Infectologist and Tropical

Medicine specialist

1, Infectologist and Tropical

Medicine specialist

Joshi Acosta

![]() 2, Medical microbiologist, doctor

of Microbiology

2, Medical microbiologist, doctor

of Microbiology

1 Instituto

Nacional de Salud, Lima, Peru.

2 Instituto de

Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación, ESSALUD, Lima, Peru.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: In Peru, despite the small number of cases, there is evidence

of late diagnosis and hidden

Materials and methods: A qualitative study was carried out, applying semi-structured

interviews to patients diagnosed with leprosy from the Loreto and Ucayali

regions.

Results: 30 patients were interviewed. Most did not know the mechanism

of leprosy transmission. In relation to therapeutic itineraries, patients

generally went to health facilities on the recommendation of third parties who

knew the disease. In some cases, health personnel made a bad diagnosis. The

importance of the treatment indicated by the “Ministerio de Salud” (Ministry of

Health) is recognized; however, economic factors and the distance to health

facilities negatively affect adherence to treatment. In addition, it was evidenced

that stigma persists towards the disease.

Conclusions: Patients recognize the importance of treatment; however, they

express misconceptions about the pathogenesis of leprosy, and weaknesses in the

health system are also identified. These problems would lead to delay in

diagnosis and treatment. It is recommended to strengthen control strategies and

decentralize the care of leprosy with the participation of the community,

patients, health personnel and healers, considering the identified barriers and

a probable underdiagnosis in women.

Keywords: Leprosy; Health services; Perception; Therapeutics; Qualitative Research; Disability; Sociodemographic Factors; Stigma; Perú (source: MeSH NLM).

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy, considered to be a worldwide public health problem, was

reportedly eliminated as of 2000. By 2005, most countries had achieved this

goal; however, in several countries, it continues to be a problem at the regional

level (1).

The Ministry of Health (MINSA in Spanish) of Peru

reported a progressive decrease in prevalence, although there are still new

cases detected. Despite this, rates of less than 1 per 10,000 inhabitants have

been achieved in the provinces.

Most of the cases are circumscribed in the Peruvian

jungle, specifically in Loreto and Ucayali, because the disease entered these

regions through the border with Brazil in the 20th century (2). In

this context, the government policies on the control of leprosy facilitated the

introduction of anti-leprosy drugs, and achieved the control of the disease,

but not its eradication (2). In 2017, the MINSA reported eleven new

cases, including some leprosy-associated grade 2 disability, which evidences a

late diagnosis and the hidden prevalence of the disease.

|

KEY MESSAGES |

|

Motivation for the study:

In Peru, a country with a low prevalence of leprosy, patients

are still diagnosed with a leprosy associated grade 2 disability, which

suggests a late diagnosed disease.

Main findings:

Since

patients do not know the mechanism of transmission of leprosy, most of them

go to hospital following the recommendation of those who identified the

disease.

Implications:

Strategies are required to control leprosy, considering the identified

limitations of the health sector and the patients’ lack of knowledge about

the disease. |

Underdiagnosis and late diagnosis are associated

with the lack of follow-up, no active search for cases and disinformation of

people and healthcare personnel, all of which have negative consequences

influencing leprosy control (3).

Due to people’s financial problems, late diagnosis

is a result of their delay in seeking medical attention (4), and

their therapeutic itinerary (what they do and where they go to maintain or

restore their health) (5). Traditional medicine should also be

considered as influencing late diagnosis since it covers different conceptions

of health and comprises the experience and cooperation of family groups and

community (6).

The search for treatment, in contexts where different healthcare systems

coexist, is influenced by the complexity, costs and sociocultural and

geographical proximity of the health offer, which means that patients can

combine the different offers of each health system (7-9).

Leprosy control also requires knowing the

therapeutic repertoires (procedures and resources) of each healthcare system

and how patients use them (10). Likewise, adequate adherence to

treatment is required; however, it depends on socioeconomic, cultural,

psychosocial, and behavioral factors, and on adverse drug reactions (11,12).

In this context, the systems of interpretation of the disease vary within and

between cultural groups, and influence the way people prevent and treat the

disease (6,13-17).

In this concern, the objective of the study was to understand the systems of

leprosy interpretation, itineraries and therapeutic repertoires of patients

diagnosed with leprosy under treatment or after completion of treatment.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

A qualitative study was carried out, using intentional

non-probability sampling, in which semi-structured in-depth interviews were

applied to leprosy patients under treatment or after completion of treatment.

The interviews took place between October and November 2015. Previously, the

interviewer and those responsible for the National Health Strategy for

Tuberculosis Component Lepra had a meeting with patients in order to explain in

a simple and clear way the purpose of the investigation.

The study included patients over 18 years old with

a leprosy diagnosis made in MINSA healthcare facilities, who resided at the

time of the study in the city of Iquitos (department of Loreto, province of

Maynas, districts of Belen, Punchana and San Juan Bautista) those who resided

in the city of Pucallpa (department of Ucayali, province of Coronel Portillo,

districts of Calleria, Yarinacocha and Manantay). The eight profiles

established for patients in each region included leprosy treatment (under treatment

or treatment completed), domicile (urban or rural), and sex (female or male).

The interviews were held by a healthcare

professional with experience in community work in several native communities

and qualitative study conduction, who had an induction regarding the research

topic by the team of researchers (anthropologist and infectious disease

experts in the management of leprosy patients). The interviewer also lived in

one of the included regions, which allowed an easier understanding with patients,

since he knew the mores and cultural terms used to communicate colloquially.

It is worth mentioning that all the interviews were carried out at patients’

homes, ensuring privacy and confidentiality.

Considering the theories of Chrisman (5),

Kleinman (6),

Young (7),

Schartz (8)

and Good (13), three study dimensions were proposed:

leprosy interpretation systems, therapeutic itineraries, and therapeutic

repertoires used by patients with leprosy diagnosis, including adherence to

treatment. A total of 20 codes were proposed for each dimension, based on the

objective and the study dimensions. In addition, the interview guide was

prepared and reviewed by an expert leprosy dermatologist and by a healthcare

worker with experience in community work, and modified according to their

suggestions. The final version of the guide was applied to people who

voluntarily decided to participate in the study. The interviews were carried

out until reaching the saturation point of information (30 interviews).

An inductive analysis was proposed, for which the

interviews were transcribed, and a content analysis of each one was carried

out, in Excel, finding information only on 16 of the 20 codes initially

proposed. During this analysis, an additional dimension of analysis was found:

the impact of leprosy on people’s lives, but it was not considered because it

was not the object of the study. The 16 analysis codes were validated by two

specialists on the subject (coordinator of the leprosy control program

nationwide and a dermatologist from the Regional Hospital of Iquitos). A

descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic characteristics of the study

subjects was performed, summarizing the numerical variables according to their

median and the categorical variables according to their percentage. Later,

researchers traveled to Loreto and Ucayali to triangulate the data and to get

feedback from the participants about the findings.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the National Institute of Health of Peru (INS in Spanish) through Memorandum

080-2015-CIEI-INS (Code OI-052-14). In addition, patients who agreed to

participate in the study were asked to sign the informed consent.

RESULTS

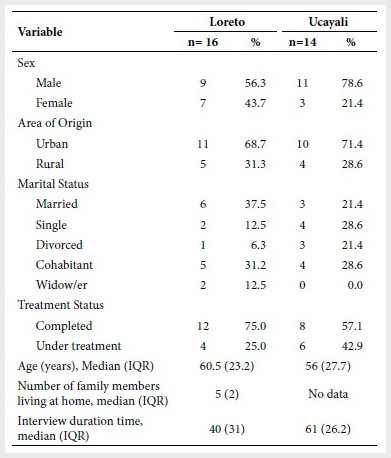

Thirty patients were included (10 of whom were women) —10 from

rural areas and 20 had completed their treatment. Most of the patients who had

completed the treatment were over 50 years old and received their first

treatment at the San Pablo leprosarium (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of patients

included in the study.

IQR: interquartile range

Interviews were conducted for the following

profiles: under treatment urban man (7 patients), under treatment urban woman

(1 patient), under treatment rural man (2 patients), urban man with treatment

profile (7 patients), urban women with treatment profile (5 patients), rural

man with treatment profile (4 patients) and rural woman with treatment profile

(4 patients). The analysis by dimensions is presented, considering the codes of

the most relevant findings. The complete analysis is attached as a supplementary

material: annex 1, 2 and 3.

Interpretation

systems on leprosy

Regardless of patient’s sex, age and area of origin, various responses were identified regarding the form of leprosy transmission, i. e., presence of a strange person or a sick person at home, washing a sick person’s clothes or shaking hands with them, sexual contact with a sick person, leaving their communities, exposure to polluting agents, such as sewage or forest diseases, or the intake of certain foods (such as the Amazonian tapir or the armadillo), “divine will”, and hereditary factors.

“Maybe my ancestors had it. You know the genetic

order, it never disappears, it follows its rhythm maybe your children don’t get

it, but your great-grandchildren may…”

55-year-old urban man from Ucayali, under

treatment.

Another perception was that the microorganisms

causing leprosy or other diseases are with the person since they are born and

it develops depending on their immune response.

Transmission by air was also mentioned by three

patients who reported that leprosy spreads when talking to an infected person;

however, they do not show security in this response, since they later justify

their contagion by other ways. It was also possible to identify that the

perception that leprosy is a highly contagious disease still present

(46-year-old rural man); while other interviewees reported that it was not

contagious (76-year-old rural woman and 78-year-old urban woman).

Regardless their area of origin and sex, patients

aged between 70 and 79 years old reported four ways to prevent spreading the

disease —not having sex with an infected person, sleeping separately, not

kissing on the mouth, burning mattresses and sheets after healing, have

separate personal supplies and eat well.

“Did you say ‘I should sleep apart’, or your wife

told you to do so? I said it should be better if I

sleep apart because maybe she can catch it from me ...”

41-year-old urban man from Ucayali, under

treatment.

Regarding the consequences of abandoning treatment,

the responses comprised relapses, death, disability and death from complications.

This speech was held by all patients regardless of their area of origin, sex

and age.

“If you stop the treatment, it can happen again, (...) maybe you

don’t take medication, you

might get sick again, death can

happen too”.

71-year-old rural woman from

Loreto, cured.

Usually the discourse used is that leprosy, following

polychemotherapy, is curable; however, an 81-year-old rural patient mentioned

that it was incurable since the disease is permanently in the blood. On the other

hand, it is recognized by patients that before there was no treatment for leprosy

and that patients died.

“Well, he told me that this disease can be cured,

it is not incurable. There is a cure, many people (...) I have talked with the

doctor then he indicated to me what it is that I must do”

58-year-old urban man from Loreto, under treatment.

Therapeutic

itineraries in leprosy

Regardless of sex and age, the patients stressed that family

support (especially from the wife) is important for them to go to a health

facility and comply with the treatment and controls. However, a 71-year-old

woman from the rural area stated that her relatives turned their backs on her

for fear of contagion. Another patient stated that his teacher identified the

spots and took him to the hospital for diagnosis.

A misdiagnosis due to the lack of experience of

health personnel can cause the patient to lose confidence and seek other

treatment options, which may lead to delayed diagnosis. This finding was

identified in two young urban patients under the age of 35.

Three patients under 50 years old (two from rural

areas and one from urban areas) with treatment completed reported having

consulted a local non-medical healer (curandero/witchdoctor) when they did not

find improvement in symptoms. A 26-year-old male patient from the urban area

mentioned that the local non-medical healer referred him to the hospital. He

stated that he did not believe in witchdoctors, but that he was taken to one by

his sisters.

“Did you go to the medicine man? Yes,

of those who cure witchcraft (...) I went because my sisters recommended me

when they saw that I had not improved. I went after the treatment, I thought

that once treatment is completed, then leprosy was over, but not really, it

takes time to disappear from your body.”

26-year-old

urban man from Ucayali, under treatment.

Regardless of the area of origin and sex, patients

think that healthcare for leprosy is limited, with difficult geographical

access and that there is a lack of specialists. Those are their barriers

against an early diagnosis and treatment.

The hospital and leprosy program were identified as

the place where the disease is primarily treated. The patients also pointed out

other places of care, such as Hospital de la Solidaridad, in Lima, the

Institute of Tropical Medicine of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos and

private clinics. Interviewees over 70 years old who completed their treatment

identified the leprosarium of San Pablo as the place of care. Pharmacies were

not recognized as options either.

“Hives have appeared (...) most people talked, and

since in Pucallpa there were also infected people who came by raft, back in

Contamana, they picked me up and took me to San Pablo.”

67-year-old rural woman from Loreto, cured.

Likewise, half of the interviewees identified a

certain MINSA doctor or technician as the person makes the diagnosis or

provides treatment (a single doctor or technician was identified for each of

the patient’s cities).

Therapeutic

repertoire of leprosy and adherence to treatment

In

relation to the treatments used, the patients indicated that they took

different types of drugs over the years, and in addition, they used vegetables,

mud and medicinal plants, such as ayahuasca, chirimasango with sacha garlic,

catahua, marco sacha, bark of cedar, etc. Treatments given by relatives or non-medical

healers.

“... and at that time my father was still living

and said to me: ‘I am going to bring you a remedy

that

is effective,’ and he brought me a jungle root named male sacha ajoma (...),

and then chirisamango. I drank a liter

of it, and that numbness disappeared for like ten years”

58-year-old urban man from Loreto, under treatment.

Patients highlighted the importance of starting

treatment early as a measure to avoid contagion or complications, but it was

also evidenced that patients have the perception that, despite having completed

treatment, leprosy could be within them and that it could manifest again.

External factors that negatively affect adherence

to treatment: living far from health centers, limited hours of attention from

health centers and limited financial resources, especially in rural patients.

Side reactions (especially gastrointestinal), patient’s lifestyle (drinking and

smoking) and presence of other diseases, such as knee joint problems, were also

mentioned, as they stated that they could not take as much medicine at the same

time (70-year-old urban man).

“No, I did not leave because I practically lived

here, I did not have the resources to go to Atalaya, to Pucallpa...”

49-year-old rural man from Ucayali, under

treatment.

Approximately half of the patients, state that they

have Health Insurance (SIS in Spanish), support from doctors and transfers to

health facilities near their town to receive treatment. Regardless of sex, area

of origin and age, it was identified that the accompaniment of the family,

especially wife and children, favors adherence. It was not possible to identify

that friends or neighbors fulfilled this role.

Regardless of patients’ area of origin, sex and

age, they reported to have avoided eating red meat, or high-fat foods, some

fish, chili or drinking beer during treatment in order not to increase liver or

kidney disorders associated with treatment. They also avoided eating fish with

bones or pork because they associate it with the appearance of lepromatous lesions.

“When you were under treatment what things did you

not eat? When I started to swallow the pills every day, I ate everything, I

just didn’t drink beer, I didn’t smoke, I didn’t eat pig, chili

...”

46-year-old rural man, with treatment completed.

DISCUSION

Most of the patients who were receiving or had received

treatment in a MINSA health facility were unaware of the way in which leprosy

spread. Although most of them associated it with a form of contagion, only

three patients mentioned airborne contagion. This could be explained by the

social representation of the disease, associated with perceptions of

incurability and contagiousness, which in turn is related to the stigma

associated with physical deformities (14,15). Most of the interviewed patients had completed

treatment, and many had sequelae, due to late initiation of treatment, or

because they contracted the disease many years ago when there was no specific

treatment, which may explain the perceptions of incurability associated with

lack of understanding and knowledge about the disease (15,16).

Despite the fact that, in our study, the interviewees stated that they were

cured thanks to polychemotherapy and recognized the consequences of abandoning

treatment, this “cured” condition from the perception of the affected person

and the community is “misleading”, because some patients continue to feel

infected, both among those with or without disabilities (15).

The study showed that the majority of the patients went to the

hospitals or smaller medical centers on the recommendation of others. The

influence of close family members in seeking help for the diagnosis of the

disease was very important. The literature indicates that the influence of

social networks motivates patients to seek the definitive diagnosis; otherwise,

the affected will not do it by themselves. This behavior could respond two

reasons: despite having previous experience with the disease, these patients

were not aware of the risk to which they were exposed, or despite suspecting

that they have leprosy, they were silent for fear of social rejection; for

these reasons, decision-making about whether or not to go to a health center

would also be influenced by accumulated negative social experiences (18,19).

In relation to the therapeutic itinerary, we found

that the quality of health services, especially, first level and private

clinics, was inefficient. In some of the cases they gave a bad diagnosis,

delaying the start of treatment; this finding agrees with Naaz, et al. where it is reported that local professionals have poor

knowledge about leprosy, although this study describes little referral to

specialized centers (15). These researchers have indicated that patients who go

to the most complex hospitals are 6.6 times more likely to receive timely treatment

(15).

However, for our reality, and in the search of the eradication of leprosy, it

is necessary to strengthen first-level health care facilities to capture

probable cases of leprosy, through dermatological screening and home contacts (20).

It is important to highlight that the majority of

patients report that health services are limited, that there are few

specialists, and in several cases, there is difficulty in accessing health

facilities, either due to the remoteness of these, or for the economic cost of

the transfer. This constitutes barriers to early diagnosis and treatment, and

make therapeutic adherence difficult.

In addition, the need to strengthen knowledge about

the disease in patients, the community and healthcare personnel has been evidenced,

lack of knowledge is associated with delay in seeking medical care and failure

to treatment adherence (21, 22). In this sense, only two patients

indicated that the initiation of treatment is very important to avoid

disability, despite the fact that the relationship between disability,

treatment and timely diagnosis is supported by various studies (15,23).

The delay in diagnosis is related to ignorance of the disease by health

personnel, therefore, it is important to reinforce education on this pathology

in professionals in the provinces with cases of leprosy (21,22).

Regarding the search for care by non-medical

healers, approximately a third sought care with non-medical healers, including

patients under treatment. This has been described in other studies, where it

was found that the majority of the study participants received the first

treatment from witchdoctors and traditional healers (18).

Currently, it has been shown that non-medical healers are trusted (although in

a limited way), creating the need to incorporate said healer as “a complementary

medical support” within the biomedical system (24), possibly to fulfill roles

of referral mediators between patients and hospitals.

Peru has a low prevalence of leprosy; therefore,

the detection of new cases should be accompanied by a strict follow-up of

contacts, social participation of those affected and the community, and in

addition to trained professionals and surveillance centers for drug resistance (20,25).

However, in our study and other previous studies, two major problems have been

evidenced: the lack of experience of healthcare personnel in detecting the

disease (15)

and disjointed work between health centers, the community, and a

specialized hospital, to control leprosy. Likewise, other studies have

described that stigma and discrimination are negative psychosocial factors

that play an important role in the elimination of leprosy; therefore, public

policies should be aimed at establishing measures that address these issues (20,25).

Among the limitations of the study, the difficulty

of obtaining at least two interviews for each profile stands out. This is

related to the decrease of new cases of leprosy in the country, and that the

new cases are scattered in remote districts. Likewise, it was observed that

there was greater difficulty in encountering female patients undergoing

treatment in both rural and urban areas, and this could limit our results

regarding their perceptions of leprosy; however, this could be explained by the

epidemiology of leprosy in the country, where according to national reports,

new cases are mostly in men. Despite the fact that the diagnosis of leprosy has

been reported to be more frequent in men than in women, this differs

statistically from other countries such as Brazil, where leprosy cases in Mato

Grosso are more frequent in women, which should be evaluated with caution due

to the possible underdiagnosis of leprosy in women (26,27).

Another important limitation of the study was that

the person who conducted the interviews did not participate in the design of

the project or in the analysis of the interviews. Despite the limitations, we

believe that the results are relevant, since similar studies have not been

conducted in Peru. These results can help strengthen leprosy elimination

strategies at the district level, considering those cities with new cases in

recent years.

In conclusion, patients recognize the importance of

leprosy treatment, however, they express misconceptions about the pathogenesis

of this disease and weaknesses in the health system are identified. These

problems would lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment of the disease. It is

recommended to strengthen control strategies and decentralize leprosy care with

the participation of the community, patients, healthcare personnel and

non-medical healers, considering the identified barriers and a probable

underdiagnosis in women. This will influence the eradication of leprosy in the

country.

Acknowledgments:

To Mg. Efraín Ayala Remón, for his support in conducting the interviews and transcription and the anthropologist Enzo Morales for his support in the analysis of the information.

REFERENCES

1. World

Health Organitation. Weekly epidemiological record

[Internet]. WHO. 2016 [citado el 4 de diciembre del 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/wer/2016/wer9135.pdf.

2. Burstein

Z. Revisión histórica del control de la Lepra en el Perú. Rev

perú med exp salud pública [Internet]. 2001 [citado el 28 de

diciembre del 2019]; 18(1-2):40-4. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1726-46342001000100010&lng=es.

3. Acosta J. Evaluabilidad del Programa de eliminación de la lepra en el

Perú [tesis de master]. Granada: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública, Universidad

de Granada; 2013.

4. Peters

RMH, Dadun, Lusli M,

Miranda-Galarza B, Van Brakel WH, Zweekhorst

MBM, et al. The meaning

of leprosy and everyday experiences: an exploration in cirebon,

indonesia. J Trop Med

[Internet]. 2013 [citado el 30 de diciembre del 2019]; 2013: 507034. Disponible

en: https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/507034.

5. Chrisman

NJ. The health seeking process: an approach to the natural history of illness. Cult Med

Psychiatry [Internet]. 1977 [citado el 14 de

diciembre del 2019];1(4):351-77. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00116243.

6. Kleinman

A. Concepts and a model for the comparison

of medical systems as cultural systems.

Soc Sci Med

[Internet]. 1978 [citado el 10 de diciembre del 2019]; 12(2B):85-93. Disponible

en: https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7987(78)90014-5.

7. Young A. The anthropologies of illness and sickness. Annu Rev Anthropol

[Internet]. 1982 [citado el 20 de diciembre del 2019]; 11:257-85. Disponible

en: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.11.100182.001353

8. Schwartz

LR. The hierarchy of resort in curative practices: The Admiralty

Islands, Melanesia. J Health Soc Behav [Internet]. 1969 [citado el 14 de diciembre

del 2019];10(3):201-9. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.2307/2948390.

9. Simionato

I, Moraes M, Viera A, Seles L, Samboni

T, Arrollo L, et al. Social determinants, their relationship with leprosy risk

and temporal trends in a triborder

region in Latin America. PLoS Negl

Trop Dis [Internet]. 2018

[citado el 7 de diciembre del 2019]; 12(4): e0006407. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006407.

10. Chamorro A, Tocornal C. Prácticas de salud en las comunidades del Salar

de Atacama: Hacia una etnografía médica contemporánea. Estud

Atacam [Internet]. 2005 [citado el 10 de diciembre

del 2019];(30):117-34. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-10432005000200007.

11. Honrado ER, Tallo V, Balis AC, Chan GP, Cho SN. Noncompliance with the world health

organization-multidrug therapy

among leprosy patients in Cebu, Philippines: its causes and implications on the leprosy control program. Dermatol Clin [Internet]. 2008 [citado el 17 de enero del 2020]; 26

(2): 221-9. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2007.11.007.

12. Heukelbach

J, Chichava OA, Rodriguez

de Oliveira A, Häfner K, Walther

F, Morais de Alencar CH, et

al. Interruption and Defaulting

of Multidrug Therapy against Leprosy: Population-Based Study in Brazil’s Savannah Region. PLoS Negl Trop

Dis [Internet]. 2011 [citado el 30 de diciembre del

2019]; 5(5): e1031. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001031.

13. Good

BJ. Medicina, racionalidad y experiencia: una perspectiva antropológica.

Barcelona: Bellaterra Ediciones Barcelona; 2003.

14. Van

Brakel WH , Sihombing

B, Djarir

H, Beise

K ,

Kusumawardhani L , Yulihane R, et

al. Disability in people

affected by leprosy: the role of impairment, activity, social participation, stigma and discrimination. Glob

Acción para la Salud [Internet]. 2012 [citado el 10 de

diciembre del 2019]; 5:10. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3402069.

15. Naaz

F, Mohanty PS, Bansal AK, Kumar D, Gupta UD. Challenges Beyond Elimination in Leprosy. Int J

Mycobacteriol [Internet]. 2017 [citado el 10

de diciembre del 2019]; 6(3):222-8. Disponible en: http://www.ijmyco.org/text.asp?2017/6/3/222/211929.

16. Sermrittirong

S, Van Brakel W, Kraipui N,

Traithip S, Bunders-Aelen

J. Comparing the perception of community members towards leprosy and tuberculosis stigmatization.

Lepr Rev. 2015; 86(1): 54–61.

17. Valsa A, Longmore M, Ebenezer M, Richard

J. Effectiveness of Social Skills

Training for reduction of self-perceived Stigma in Leprosy Patients in rural India -

a preliminary study. Lepr Rev. 2012; 83(1): 80- 92.

18. Adhikari

B, Kaehler N, Chapman RS, Raut

S, Roche P. Factors Affecting

Perceived Stigma in Leprosy Affected Persons in Western Nepal. PLoS

Negl Trop Dis

[Internet]. 2014 [citado el 7 de diciembre del 2019]; 8(6): e2940. Disponible

en: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002940.

19. Susanti

IA, Mahardita

NGP, Alfianto

R , Sujana IMIWC , Siswoyo , Susanto T. Social stigma, adherence to medication

and motivation for healing: A cross-sectional study of leprosy patients at Jember Public Health

Center, Indonesia. J Taibah Univ

Med Sci [Internet]. 2017

[citado el 5 de diciembre del 2019]; 13 (1): 97-102. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.06.006.

20. Li J, Yang L, Wang Y, Liu H, Cross H. How to improve early case detection in low endemic areas with

pockets of leprosy: a study of newly detected leprosy patients in Guizhou Province, People’s Republic of China. Lepr Rev. 2016; 87(1): 23-31.

21. Martins

RJ, Oliveira ME, Saliba SA, Saliba

SA, Ísper AJ. Sociodemographic

and epidemiological profile

of leprosy patients in an endemic region

in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med

Trop [Internet]. 2016 [citado el 5 de enero del

2020]; 49(6):777-780. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0069-2016.

22. Lira

KB, Leite

JJ, Maia DC, Freitas R , Feijão AR. Knowledge of the patients

regarding leprosy and adherence to treatment. Braz J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2012 [citado el 11 de enero del 2020];

16(5):472-5. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.04.002.

23. Matos

AMF, Coelho

ACO ,

Araújo LPT, Alves MJM, Baquero OS, Duthie MS, et al. Assessing epidemiology of leprosy and socio-economic distribution of cases. Epidemiol

Infect [Internet]. 2018 [citado el 7 de diciembre del 2019];

146(14): 1750-55. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818001814.

24. Eysaguirre

CF. El proceso de incorporación de la medicina tradicional y alternativa y

complementaria en las políticas oficiales de salud [tesis de máster]. Lima:

Facultad de ciencias sociales, Universidad Mayor de San Marcos; 2016.

Disponible en: http://cybertesis.unmsm.edu.pe/handle/cybertesis/6274.

25. Cairns

W, Smith S. Leprosy: making

good progress but hidden challenges

remain. Indian J Med Res [Internet]. 2013 [citado el 11 de enero del 2020];

137:1-3. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3657869/.

26. Zhang F, Chen S, Sun Y, Chu T. Healthcare seeking behaviour and delay in diagnosis of leprosy in

a low endemic area of China. Lepr Rev [Internet]. 2009 [citado el 11 de enero del 2020];

80(4):416-23. Disponible en: https://www.lepra.org.uk/platforms/lepra/files/lr/Dec09/Lep416-423.pdf.

27. Walker SL, Withington SG, Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy. En: Farra J, Hotez P, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo, White N, editores. Manson’s

Tropical Infectious Diseases

[Internet]. 23a ed. 2014 [citado el

12 de enero del 2020]. p 506-18 Disponible en: https://www.elsevier.com/books/mansons-tropical-infectious-diseases/9780702051012-

Funding:

The research was funded by the 2014 Competitive Fund of the National Center for

Public Health of the National Institute of Health of Peru.

Supplementary

material:

Available in the electronic version of the PSRP

Citation:

Osorio-Mejía C, Falconí-Rosadio E, Acosta J. Interpretation

systems, therapeutic itineraries and repertoires of leprosy patients in a low

prevalence country. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica.

2020;37(1):25-31. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4820

Correspondence to:

Carmen Edith Osorio Mejía; Av. Defensores del Morro 2268, Chorrillos.

Lima, Perú;

caome22@gmail.com

Authorship contributions: JA and

EFR have participated in the conception and design of the study. JA and COM

participated in the collection, analysis of data and writing of the article. In

addition, JA participated in the obtention of funding. All three authors

approved the final version of the article.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare to have no

conflicts of interest in relation to this publication.

Received:

20/09/2019

Approved:

22/01/2020

Online:

19/03/2020