BRIEF REPORT

Cost variability of antipsychotics according to pharmaceutical

establishments in Lima, Peru

Rubén

Valle ![]() 1,2

, Psychiatrist,

Master of Science in Epidemiological Research

1,2

, Psychiatrist,

Master of Science in Epidemiological Research

1

Centro de Investigación en Epidemiología

Clínica y Medicina Basada en Evidencias, Facultad de Medicina Humana,Universidad

de San Martín de Porres, Lima, Peru.

2 DEIDAE de Adultos y Adultos Mayores,

Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental «Honorio Delgado - Hideyo Noguchi», Lima,

Peru.

ABSTRACT

The

objectives of the study were to determine the cost variability of

antipsychotics in public (hospitals) and private pharmaceutical establishments

(pharmacies and clinics), calculate the cost variability of antipsychotics

between establishments and estimate the cost of monthly maintenance treatment

with antipsychotics. A cost analysis study was performed, unit costs of

antipsychotics were obtained from the Peruvian Pharmaceutical Products

Observatory. The results show that the cost variability of antipsychotics was

greater in pharmacies and clinics than in hospitals, and the analysis of cost

variability between pharmaceutical establishments showed that the cost of an

antipsychotic in a pharmacy and clinic was 1.3 to 140 times and 2.8 to 124

times, respectively, the cost of the drug in a hospital. The cost of monthly

maintenance treatment varied from S/ 3 to S/ 2130 according to the drug and

pharmaceutical establishment.

Keywords: Costs and Cost analysis; Antipsychotic Agents; Schizophrenia; Mental Disorders; Peru (source: MeSH NLM).

INTRODUCTION

Antipsychotics are a group of drugs used in the

treatment of various mental disorders. These drugs are considered the cornerstone

of treatment for psychotic disorders (1). Some of these have been

approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder (2), or are used in an

unapproved way in the obsessive-compulsive disorder and personality disorder (3,4).

Antipsychotics are effective in reducing the symptoms of psychosis and differ

in the profile of side effects they can produce (5). These drugs should

be taken daily (oral) or periodically (deposit) to avoid relapses and to help

in the recovery process (6,7). It is therefore

important that health systems can ensure access to these drugs.

Patients

recibing antipsychotics, who are users of the Integral Health Insurance (SIS),

receive the drugs free of charge in the Ministry of Health (MINSA) facilities.

However, access to these drugs in MINSA institutions is limited since only 78%

of the institutes, 64% of the hospitals, 8% of the centers, and 1% of the

medical posts have antipsychotics (8). This situation leads

patients to buy their medicines in private pharmacies at a higher cost, with

the consequent increase in out-of-pocket expenses (8). Relapses can also

occur because of reducing the dose or even discontinuing treatment because

patients cannot afford it. Clinical relapses, in turn, lead to higher expenses

for the health system due to the use of more expensive services such as

emergency or hospitalization (9).

The

costs of antipsychotics vary widely in the marketplace. The cost variability

(ratio of lowest to highest cost) of risperidone in India is 1 to 16, and

olanzapine 1 to 12; the variability of these drugs in Brazil is 1 to 35,000 and

1 to 79, respectively (10,11). Antipsychotics can have high costs,

which results in less access to these drugs and the possibility that patients

may not be able to continue treatment. In Peru, one report showed wide

variations in the cost of drugs, with the cost of a drug being ten times higher

in a private pharmacy than in a public one (12). However, the variability of

antipsychotic costs has not been specifically studied.

|

KEY MESSSAGES |

|

Motivation for the study:

Although antipsychotics are useful for the

management of several mental disorders and must be taken for a long time,

these can be expensive, making access to these medicines difficult.

Main findings:

The unit cost and monthly treatment with antipsychotics is

higher in pharmacies and clinics than in hospitals. The cost of monthly

treatment varies from S/3 to S/2,130 depending on the drug and pharmaceutical

establishment.

Implications:

Public hospitals must ensure that they have enough

antipsychotics supply so that users of these drugs do not have problems in

obtaining them. |

The

objectives of the study are to determine the variability of antipsychotic costs

in public (hospitals) and private (pharmacies and clinics) pharmaceutical

establishments, to estimate the variability of antipsychotic costs between

pharmaceutical establishments and to estimate the cost of monthly treatment

maintenance with antipsychotics in monotherapy.

THE STUDY

This is a cost analysis partial economic study

according to the user’s perspective. The unit costs of antipsychotics were

obtained from the Peruvian Observatory of Pharmaceutical Products (OPPF) of the

General Directorate of Medicines, Supplies and Drugs (DIGEMID), where

pharmaceutical establishments post information on the costs of drugs (13).

Peru’s Single National Request for Essential Medicines contains the generic

names of the antipsychotics entered into the search engine, other antipsychotics

used in psychiatric care were also included (14). The search provided information

on the pharmaceutical establishment, date of data update, product name,

laboratory name, unit cost, and technical information of the product.

Public

pharmaceutical establishments in MINSA and DIGEMID hospitals were categorized

as “hospitals”; pharmaceutical establishments like apothecaries and private

pharmacies were categorized as “pharmacies”; and pharmaceutical establishments

such as private clinics were categorized as “clinics”. In addition,

antipsychotics whose name corresponded to the International Non-proprietary

Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN) were categorized as “generics”; those

whose name corresponded to the drug studied in a pharmacological research and

which obtained the patent were categorized as “innovative drugs”; and antipsychotics

which were listed under a trade name, but different from that of the innovative

drugs, were categorized as “branded generics” (15).

The

descriptive analysis consisted of calculating the median, minimum and maximum

value of the cost of the antipsychotic according to the type of drug and

pharmaceutical establishment. The cost variability analysis by antipsychotic

compared the minimum and maximum cost of an antipsychotic of the same

formulation dispensed by the same type of pharmaceutical establishment. The

analysis of cost variability between pharmaceutical facilities compared the

median cost of an antipsychotic in a hospital with that of a pharmacy and a

clinic. The estimate of the cost of monthly maintenance treatment with

antipsychotics in monotherapy was made based on the upper limit of the

maintenance dose range of each antipsychotic according to the international

consensus study on dosage (16). The analysis was performed with the

statistical program Stata v12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

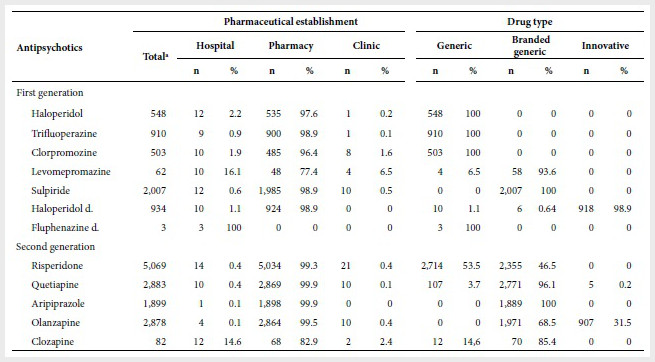

Data on 11 antipsychotics was available from the OPPF

as of July 5th, 2019: six of first-generation and five of second-generation.

Data had been entered at the OPPF between May 5th and July 4th, 2019. Only

three antipsychotics were available as innovative drugs: haloperidol decanoate

(Haldol decanoes), quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa). The data

were reported mostly by pharmacies (77.4%-99.9%), followed by hospitals

(0.1%-100%) and clinics (0.1%-6.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Availability

of antipsychotics by pharmaceutical establishment and type of drug in Lima

a

Establishments that supply antipsychotics according to the Peruvian Observatory

of Pharmaceutical Products. d: decanoate.

Antipsychotic costs

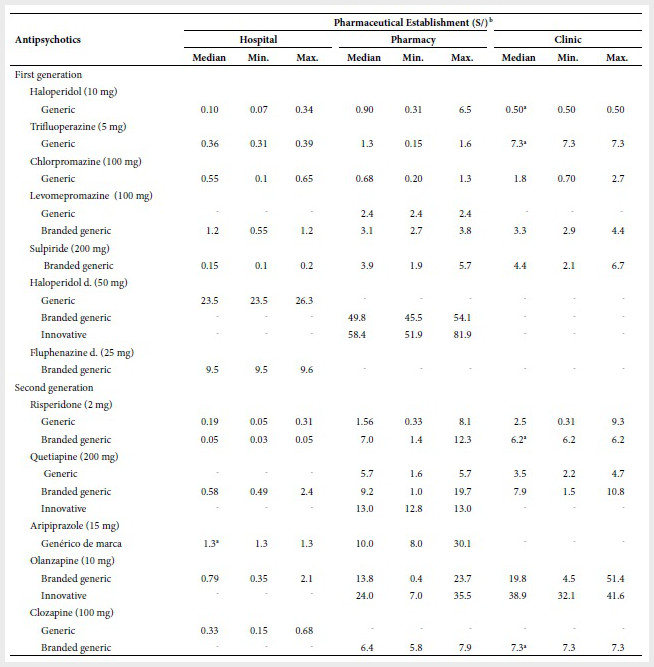

The median of the unit costs of oral antipsychotics

was lower in hospitals than in pharmacies and clinics. Median costs of antipsychotics

in hospitals ranged from S/ 0.1 (haloperidol) to S/ 1.3 (aripiprazole), in

pharmacies from S/0.68 (chlorpromazine) to S/ 24.0 (olanzapine) and in clinics

from S/ 0.5 (haloperidol) to S/ 38.9 (olanzapine). The median costs of generic

antipsychotics were lower than branded generic ones (except for risperidone

sold in hospitals), and their costs were lower than those of the innovative

drugs. This trend was also observed for haloperidol decanoate. Fluphenazine

decanoate was only available in hospitals at a (median) cost of S/ 9.5 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unit cost of antipsychotics according to pharmaceutical establishment and type

of drug in Lima

a

There was only one observation; b costs less than S/1 are

represented with two decimals.

d:

decanoate; Min.: minimum; Max.: maximum; hyphen (-): no data was reported.

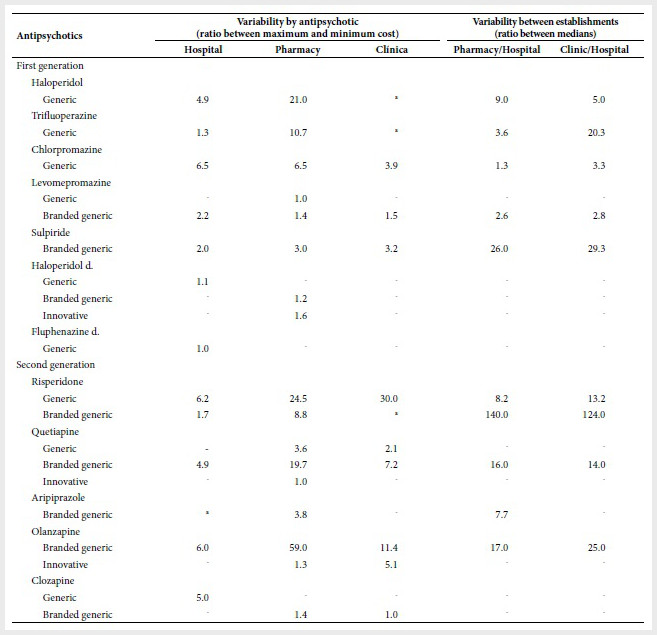

Cost variability by antipsychotic, and between

pharmaceutical establishments

The greatest variability in hospital costs was 1 to

6.5 for generics (chlorpromazine) and 1 to 6 (olanzapine) for brand generics.

In pharmacies, the greatest variability in generics was 1 to 24.5

(risperidone), in branded generics was 1 to 59 (olanzapine) and in innovative

drugs was 1 to 1.6 (haloperidol decanoate). In clinics, the highest variability

in generics was 1 to 30 (risperidone), in branded generics was 1 to 11

(olanzapine) and in innovative drugs was 1 to 5.1 (olanzapine).

The

greatest variability in costs between hospitals and pharmacies was described

for haloperidol (1 to 9) and in branded generics for risperidone (1 to 140).

Between hospitals and clinics, the highest cost variability regarding generics,

was for trifluoperazine (1 to 20.3) and in branded generics was for risperidone

(1 to 124) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost

variability by antipsychotic and among pharmaceutical facilities in Lima

a

There was only one observation.

d:

decanoate, Min.: minimum, Max.: maximum; hyphen (-): no data was reported.

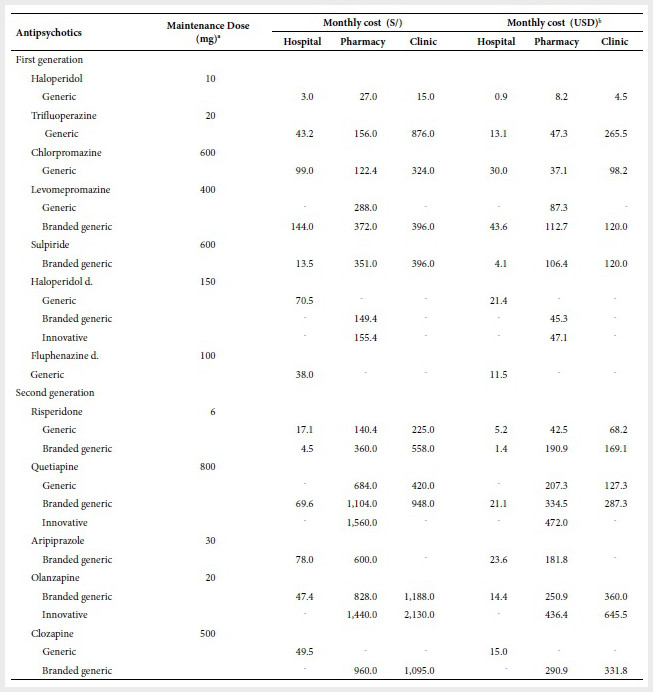

Cost of monthly treatment

The maintenance cost of monthly treatment with

antipsychotics was lower in hospitals than in pharmacies and clinics. The

monthly treatment cost varied from S/ 3 (generic/ haloperidol) to S/ 144

(levomepromazine/branded generic) in hospitals, from S/ 27 (haloperidol/generic)

to S/ 1,560 (olanzapine/innovative) in pharmacies from S/ 15

(haloperidol/generic) to S/ 2,130 (olanzapine/innovative) in clinics. Treatment

cost in pharmacies and clinics with generic, risperidone, quetiapine and

levomepromazine (pharmacies only) was higher than with their branded generics

in hospitals. The cost of monthly treatment in hospitals with haloperidol

decanoate (S/ 70.5) was almost double that of fluphenazine decanoate (S/ 38)

(Table 4).

Table 4.

Estimate

of monthly cost of maintenance treatment with antipsychotics

a

Based on the international consensus study on antipsychotic dosage (16).

The doses are not necessarily comparable. b

Exchange rate: 1 USD= S/3.3.

d:

decanoate; hyphen (-): no data was reported.

DISCUSSION

The study provides an economic perspective on the

cost of antipsychotics and the treatment cost of these drugs. The results show

that the cost variation is greater in private pharmaceutical establishments

(pharmacies and clinics) rather than in public establishments (hospitals). The

selling price of a drug in this sector cannot exceed 25% of its purchase price (17) this could be the cause for the small

variability of antipsychotic costs in hospitals. While the high variability of

costs in pharmacies and clinics could be due to the lack of regulation in the

antipsychotic drug costs (18). Thus, the different type of regulation

between the public and private sectors would explain the differences in the

variability of the costs of antipsychotics.

It

has been argued that the higher cost in private establishments is because these

centers sell “brand” medicines with a purchase cost higher than that of the

generic ones (12), and because the public sector makes corporate

purchases that allow the public sector to sell medicines at a low cost. In

contrast, our study shows that some generic branded antipsychotics in hospitals

cost less than their generic counterparts sold in pharmacies and clinics. In

addition, private pharmacies in Peru have had a merger process that allows them

to manage a large part of the market and therefore make corporate purchases (18). In

this sense, the high cost of antipsychotics in pharmacies and clinics seems to

be exclusively due to market laws and the search for higher profit margins.

The

estimate of the cost of monthly maintenance treatment was made based on a

monotherapy scheme when polypharmacy, the joint use of more than one

psychotropic drug, is more common (19). Polypharmacy is not

supported by evidence and adds higher treatment costs by adding an

antipsychotic or other psychiatric drug to the therapeutic scheme; however, it

is widely used in our setting. For example, two studies in patients with

schizophrenia showed that 40.5% of outpatients and 57% of inpatients received

more than one antipsychotic (20,21). Therefore, the treatment costs in

our study only apply to monotherapy treatment and not to polypharmacy

treatments whose cost would be higher.

The

study has some limitations. A report from the Ombudsman’s Office found that the

coincidence between the cost of medicines in pharmacies and the OPPF was 69.3%

(12),

so it is likely that a percentage of the costs of antipsychotics from the OPPF

may be different from the costs they have in pharmacies due to a lack of an

update or under-reporting by pharmacies. The estimate of the cost of monthly

maintenance treatment was made on the basis of recommended doses and not the

prescribed doses, so our estimates may differ from the actual cost of

treatment. The inference of our results could be affected if establishments

selling antipsychotics do not report them to the OPPF; however, this

probability is low since only 6.2% of pharmacies are not registered in the OPPF

(12).

On the other hand, the data from the OPPF allowed to overcome problems of reluctance

on the part of pharmacies to provide information on the costs of medicines (22),

and allowed to know the cost of antipsychotics from a large number of

pharmacies that otherwise would have taken high resources.

In conclusion, the results show that the cost variability of antipsychotics is greater in pharmacies and clinics than in hospitals, and the analysis of cost variability between pharmaceutical establishments shows that the cost of an antipsychotic in a pharmacy and clinic can be as much as 1.3 to 140 times and 2.8 to 124 times the cost of the drug in a hospital, respectively. The cost of monthly treatment with antipsychotics in monotherapy varies from S/ 3 to S/ 2,130 depending on the type of drug and pharmaceutical establishment. The wide variability of antipsychotic costs identified in our study demands that some me-asures should be taken. The mental health authorities must ensure the supply of antipsychotics in MINSA institutions so that the SIS-affiliated population using these drugs can always receive them, and that users not affiliated to the SIS can buy them at these centers. In addition, health authorities should consider regulating the cost of antipsychotics in the private market, as is the case in other countries. Finally, physicians who prescribe antipsychotics should know the costs of these drugs, assess the cost of antipsychotics before prescribing them and comply with the technical standard of prescribing generic drugs.

REFERENCES

1. Kreyenbuhl

J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB, Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94–103.

doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp130.

2. Frye

MA. Clinical practice.

Bipolar disorder--a focus on depression. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):51–9. doi:

10.1056/NEJMc1101370.

3. Zhou

D-D, Zhou X-X, Lv Z, Chen X-R, Wang W, Wang G-M, et al. Comparative

efficacy and tolerability

of antipsychotics as augmentations

in adults with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive

disorder: A network meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111:51–8. doi:

10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.01.014.

4. Stoffers

J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):1–166. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

5. Leucht

S, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. Evidence-based

pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia.

Int J Neuropsychopharmacol.

2011;14(2):269–84. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001380.

6. Kishi

T, Ikuta T, Matsui Y, Inada K, Matsuda Y, Mishima K, et al. Effect of discontinuation v. maintenance of

antipsychotic medication on relapse rates

in patients with remitted/stable first-episode psychosis: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(5):772–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001393.

7. Guo

X, Zhang Z, Zhai J, Fang M,

Hu M, Wu R, et al. Effects of antipsychotic medications on quality of life and psychosocial functioning in patients with early-stage

schizophrenia: 1-year follow-up

naturalistic study. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(7):1006–12. Doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.003.

8. Hodgkin

D, Piazza M, Crisante M, Gallo C, Fiestas F. Availability of psychotropic medications in health care facilities of the Ministry of Health of Peru, 2011. Rev Peru Med

Exp Salud Publica. 2014;31(4):660–8.

9. Pennington

M, McCrone P. The Cost of Relapse in Schizophrenia. PharmacoEconomics.

2017;35(9):921–36. doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0515-3.

10. Shukla

AK, Agnihotri A. Cost analysis of antipsychotic drugs available in India. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2017;6(3):669–74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20170834.

11. Razzouk

D. Cost variation of antipsychotics in the public health system

in Brazil. J Bras Econ Saude. 2017;9((Suppl.1)):49–57. doi:

10.21115/JBES. v9.suppl1.49-57.

12. Defensoría del Pueblo.

Reporte Derecho a la salud [Internet]. Lima: Defensoría del Pueblo; 2018

[citado el 4 de julio de 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Reporte-Derecho-a-la-Salud.pdf.

13. Observatorio Peruano de

Productos Farmacéuticos [Internet]. Lima: Dirección General de Medicamentos,

Insumos y Drogas; 2019 [citado el 5 de julio de 2019]. Disponible en: http://observatorio.digemid.minsa.gob.pe/.

14. Ministerio de Salud.

Petitorio Nacional Único de Medicamentos esenciales para el sector salud

[Internet]. Lima: Dirección General de Medicamentos, Insumos y Drogas; 2015

[citado el 6 de julio de 2019]. Disponible en: http://www.digemid.minsa.gob.pe/UpLoad/UpLoaded/PDF/Normatividad/2018/RM_1361-2018.pdf.

15. Díez MV, Errecalde MF. Aclaraciones al concepto de genérico. Inf Ter Sist Nac

Salud. 1998;22(3):68–72.

16. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus

study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-93.

17. Ministerio de Salud.

Directiva Administrativa N°249- MINSA/2018/DIGEMID Gestión del sistema

integrado de suministro público de productos farmacéuticos, dispositivos

médicos y productos sanitarios-SISMED [Internet], 2018 [citado el 7 de julio de

2019]. Disponible en: http://www.digemid.minsa.gob.pe/UpLoad/UpLoaded/PDF/EAccMed/Normatividad/E03_RM_116-2018.pdf.

18. Huarag

E. ¿Un remedio peor que la enfermedad? sobre concentraciones, monopolios y

acceso a los medicamentos. Pluriversidad. 2018;1(1):111–26. doi:

10.31381/pluriversidad.v1i1.1674.

19. Kukreja

S, Kalra G, Shah N, Shrivastava A. Polypharmacy in psychiatry: a review. Mens Sana Monogr. 2013;11(1):82–99. doi:

10.4103/0973-1229.104497.

20. Stucchi-Portocarrero

S, Saavedra JE. Polifarmacia psiquiátrica en personas con esquizofrenia en un

establecimiento público de salud mental en Lima. Rev Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2018;81(3):145–53.

doi: 10.20453/rnp.v81i3.3382.

21. Bojórquez Giraldo E,

Arévalo Alván A, Castro Cisneros K, Ludowieg Casinelli L, Orihuela

Fernández S. Patrones de prescripción de psicofármacos en pacientes con

esquizofrenia y trastornos relacionados internados en el Hospital Víctor Larco

Herrera, 2015. An Fac Med. 2017;78(4):386–92. doi: 10.15381/anales.v78i4.14258.

22. Miranda J. El mercado de

medicamentos en el Perú ¿libre o regulado? Lima: Consorcio de Investigación

Económica y Social [Internet]. Lima: Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas; 2004

[citado el 10 de julio de 2019]. Disponible en: https://www.mef.gob.pe/contenidos/pol_econ/documentos/Medicamentos_competencia.pdf.

Funding

Sources:

Self-funded.

Citation:

Valle

R. Variabilidad de costos de antipsicóticos según establecimientos

farmacéuticos en Lima, Perú. 2020;37(1):67-73. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4899.

Correspondence to:

Rubén Valle; Av. Alameda del

Corregidor 1531, La Molina, Lima 15024, Perú;

ruben_vr12@hotmail.com;

(511) 365-2300.

Authorship contributions:

VR conceived and designed the study, collected the data, analyzed

and interpreted the results, wrote the article and approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest:

The author claims no conflict of interest.

20/10/2019

Approved:

12/02/2020

Online:

23/03/2020