Andrés A. Agudelo-Suárez

Diego A. Restrepo-Ochoa

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Relations established by women during pregnancy,

delivery and postpartum with health personnel according to social class in

Bogotá: qualitative study

Libia

A. Bedoya-Ruiz ![]() 1,

Physician, Master in Public

Health

1,

Physician, Master in Public

Health

Andrés

A. Agudelo-Suárez ![]() 1,2, odontologist, doctor of Public

Health

1,2, odontologist, doctor of Public

Health

Diego

A. Restrepo-Ochoa ![]() 1,3, psychologist, doctor of Public

Health

1,3, psychologist, doctor of Public

Health

1 Escuela de Graduados, Universidad CES,

Medellin, Colombia.

2 Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de

Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia.

3 Facultad de Psicología, Universidad CES,

Medellin, Colombia.

This research is an academic product from: Bedoya Ruiz LA. Composition of the relationship of women in pregnancy, labor and postpartum with healthcare services at different levels according to social class. Bogotá, Colombia. [Doctoral thesis]. Medellín: Escuela de Graduados, Universidad CES de Medellín; 2020.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To understand the relationship

established between women in a situation of pregnancy, childbirth and

postpartum with the health services personnel according to social class in

Bogotá (Colombia).

Materials and methods: Qualitative study. Critical

hermeneutical perspective and critical ethnography. Theoretical sampling.

Analysis by triangulation in Atlas.ti. 9 women and 8 health professionals

participated. 38 in-depth interviews were conducted for 13 months and 62

accompaniments to the maternal in the activities of prenatal control,

vaccination, labor, postpartum consultation, follow-up exams, prophylactic pisco

course, hospitalization and waiting room, both in public services as private.

Results: There are inequalities according to social class in which the

relationship between women and staff is configured in the following aspects:

permeability to the needs of women, recognition of psychosocial aspects, having

different points of view against a medical recommendation and right to complain

or demand to improve.

Conclusions: The situation described above intensifies gender issues in women with a less advantageous social class. It is necessary to develop interventions in educational and health institutions that consider aspects where human resources are sensitized on social issues related to the theoretical proposals of research and the democratization of medical information. It is unfair that the condition of social class and gender affects the quality of care and economically stratifies people’s rights.

Keywords: Social Class; Interpersonal

Relations; Pregnancy; Childbirth; Postpartum Period (source:

INTRODUCTION

There is evidence from all over the world demonstrating

mistreatment of women during pregnancy, labor and postpartum (PLP) by

healthcare personnel (1,2). Even when public healthcare programs were introduced

to implement respectful maternity care, the effects of these interventions were

not satisfactory in all cases —physical abuse decreased, but other situations

such as verbal abuse, neglect, and abandonment (1) did not.

The relationship between healthcare personnel and

women during PLP is also a concern in Colombia, where investigations carried

out revealed obstetric and gender violence (3-8). Previous studies, which

were carried out with women of different educational levels, failed to evidence

the inequalities in relationships depending on social classes. This shows

conceptual and methodological gaps in public healthcare research on this topic (9),

making it necessary not only to deepen into the indicators of maternal

morbidity and mortality, but also to the quality of health care.

|

KEY MESSAGES

|

|

Motivation for the study:

It is important to evidence the gaps in the literature, taking

into account that women in pregnancy, labor and postpartum are frequently

overlooked as subjects by health professionals.

Main findings:

There

are inequalities in the relationship that women establish with healthcare

personnel according to social class.

Implications: Alternatives must be found in the care process that transcend

the traditional biomedical model. Health policies require important

transformations in the medical and health education system. |

This study is specifically based on theories proposed by Breilh

and Menéndez (10-13). On the one hand, Breilh’s position is neo-Marxist,

that is to say, social class is not a personal choice but determined by

structural aspects. Thus, health inequalities reflect social inequalities. In

this sense, social class is understood as a group of people who share common

interests but have different levels of power, depending on their hierarchies in

the work process, and this determines their ability to accumulate wealth (10,11).

On the other hand, Menéndez focuses on critical

medical anthropology, based not only on cultural differences (seen as a barrier

between the biomedical system and the popular medical system), since it is also

necessary to include aspects related to poverty and social inequalities (12,13).

The concept of a hegemonic medical model not only ideologically excludes the

knowledge historically constructed by the subjects, but also ignores the

poorest people and ethnic groups (12,13).

On the basis of the above said, the objective of this study was to understand the relationship established between women during PLP with healthcare service depending on social class in the city of Bogota (Colombia).

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

Qualitative

and flexible study (18,19) carried out with a theoretical and methodological

approach, modified according to findings during the fieldwork. It was detailed

in a methodological report (19) and reviewed by the research committee and

external evaluators (reliability and auditability).

Phases of the

study and participants

The exploration began in May 2017, and the fieldwork began in

November 2017 and ended in December 2018. This phase consisted on personal

interviews as well as virtual communications through social networks, which

created an environment of trust among the participants —the subjects could

freely express their thoughts whenever they wanted. The analysis and writing of

the information began during the fieldwork and ended in November 2019.

During this phase of the study, nine women from the

city of Bogota, at least in the first trimester of pregnancy, and eight

healthcare professionals whose sociodemographic characteristics are summarized

in Tables 1 and 2. Women with mental illnesses or disabilities, minors and

those who could change their residence did not participate. Women and

healthcare personnel were contacted through social networks and the public

sector prenatal monitoring service, three women refused to participate because

they did not need the proposed support.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic

characteristics of pregnant women participating in the research. Bogota

a Socioeconomic status. There are 6 status considered in Colombia, with 1 being the lowest and 6 the highest. This stratification is made according to the place of housing.

b Although two women have

complementary plans, the companies that provide the healthcare services are

different and therefore the clinics are different. This is also the case in the

contributory and subsidized regime. Therefore, the first letter is placed to

make visible the companies that are different. c

Families that have the capacity to sabe and receive income from sources other

than work (rentals, equipment rental). d

Subsidized EPS. e Financial fund. f Vulnerable localities in the south of Bogotá

with worse maternal and fetal health indicators, environmental contamination,

deficit of public transport, insecurity, deficit of health services, prolonged

transfers between home and

Table 2.

Characteristics

of healthcare personnel with experience in maternal care participating in the

study, Bogota.

F: Female; M: Male

Procedure

Epistemological perspective

This

perspective considered critical hermeneutics, i. e., elements from hermeneutics

and elements from critical theory. Gadamer explains that the interpretation of

hermeneutics is not “a reproduction of an original production” but a

researcher-researched mediation, therefore it requires understanding, which is

far from objectivity. Preconceptions are built by life experiences; this

concept determines the way in which a subject can be interpreted (14).

Habbermas combines interpretation and critical theory that requires objectivity

to analyze the material conditions of the population. This author argues that

preconceptions are not always legitimate, because traditions can be imposed,

interpretation should serve to criticize ideology. Even if necessary, for understanding

the subject’s point of view, interpretation also reveals power relationships

that allow developing emancipation (15). The foregoing accounts for

the complexity of epistemology —bricoleur researchers do not limit themselves

to produce meanings of pure hermeneutics, since they can generate a resistance

to the transformation of social conditions (16).

Method

Critical

ethnography from Menendez’s relational approach that links micro-social

(relationship between subjects) and macro-social aspects (structural

conditions) (13),

and Sheper-Hughes’ position regarding the role of the researcher, who does not

try to blend in with the population, but rather realizes that his or her

presence in the community will transform his or her life and that of the

subjects of study, for this reason, it questions in a respectful and critical

manner, the health situations normalized by the population, which are aspects

that contribute to oppression in the midst of poverty and inequality. However,

this dialogue is bilateral, since it also allows the population to question it

and things are learned from this as well (17).

Quality criteria

Credibility and reliability were evaluated (13,18,19),

taking into account the participation of the main researcher who could change

the subjects’ behavior. During the fieldwork, situations affecting women’s

sexual and reproductive rights were revealed. In some cases, the participants

normalized this situation and did not see the problem; in other cases, they

sought help from the researcher. The principal investigator provided documented

information related to rights, helped to clarify medical terms, asked questions

about their wishes and opportunities, and contacted support networks on sexual

and reproductive healthcare and state institutions that monitor health care

services. It all was done for women to have tools when making their own

decisions so themselves, not the researcher, could be the transformers of the

situations that occurred in the healthcare services, all of which is consistent

with the epistemological paradigm chosen. The reference framework was built

throughout the research process, which allowed, at the end of the research, the

analysis of the results from different theoretical perspectives (credibility).

In the writing process, the discourses of the

actors were differentiated from the analyses carried out by the researcher. The

information recorded was made available to external evaluators who so they can

verify the results found (reliability and auditability).

Sampling

Theoretical

sampling (19),

taking into account Breilh’s concepts of social class (10,11) and the type of health affiliation in Colombia

(20).

Three categories were differentiated according to the work situation related to

social class (21): subsidized regime (women with informal work,

population without payment capacity), basic contributory regime (salaried

women), and prepaid contributory regime or plans complementary (salaried women

or businesswomen with the ability to pay for private services).

Methodological strategies and techniques

Three to five in-depth interviews were conducted per woman

during the PLP (with a live newborn) and information was collected at different

points in the research process (credibility). Counting the healthcare

personnel, there were a total of 38 interviews.

The interviews were carried out by the main

researcher in an unstructured way with open questions (22). A

guide was used that included topics related to social class (9-11) and the meanings of the relationship of women

with healthcare personnel (9,12). The meetings were scheduled

according to the availability of the participants in places chosen by them. The

conversations were private and confidential: in social organizations, the home

when the women were alone, and little frequented restaurants. The duration was

one hour on average.

The main researcher carried out the participant

observation (13,23) in the health services where the women

attended (Table 1). 62 women were accompanied during pregnancy, labor and

postpartum. The observations were recorded in a field diary. We sought not to

block interaction with subjects. The complete writing was done when not in the

field. Accompaniment itineraries were constructed in an ethnographic manner,

with descriptive and detailed information (credibility) that included: point of

view of each woman (visibility of the PLP process in a historical and situated

context), the position of other subjects different from the participants

(credibility), the established dialogues and the reflexivity of the researcher.

Statistical and epidemiological information was collected and it was used to

build the context of the research, which helped to give meaning to the results.

All of the above is available at Escuela de Graduados of Universidad CES in

Medellin to inform of the transferability to other Latin American urban

contexts with similar health systems.

Qualitative

analysis

Similar and different aspects among participants were identified

in the accompaniment itineraries. This information was organized during the

PLP, which allowed us to see recurrence of theoretical aspects over time by

each woman (23).

The above was transcribed in an Excel file which was important to analyze the

interviews, since there were aspects that seemed to be non-recurring, but when

triangulated (credibility) with the accompaniment itineraries, they acquired

theoretical importance.

The interviews were recorded by the main researcher

and transcribed by two female transcribers from Universidad CES in Medellin.

The transcriptions of the interviews and the accompaniment itinerary were given

to the participants for feedback.

ATLAS.ti 7 was used for the analysis; a code was

assigned to the paragraphs or phrases, which allowed classifying the information.

We disaggregated data so we could link them again but in a different way, in

the form of categories. This was done seeking to construct concepts related to

the theory (content analysis) and group data that have similar meanings, in

order to construct concepts that give meaning to the results (24). We

could identify 179 codes derived from the data and organized them in 11

categories. Two categories are published in the results of this article. The

coding process was carried out with the research group and a social worker.

The results were triangulated taking into account

the methodological techniques (credibility) and the socialization process (18,19).

This was carried out with peer researchers from Universidad CES and experts in

the field, outside the process, which allowed the inclusion of different and

interdisciplinary perspectives (reliability, auditability). Likewise, the

socialization was progressive with the participants to validate the information

and propose strategies that emerge from themselves.

Ethical aspects

We

obtained the approval of Universidad CES Ethics Committee (Act No. 99/2016) and

the Secretary of Health of Bogota (Act No. N0041000/2017). According to the

Colombian Code of Medical Ethics, the clinical decisions made by healthcare

personnel were respected in the medical field, since the attention given by

healthcare workers excluded the possible medical attention required from the

principal investigator. In the informed consent, it was clarified who the

researcher was and her interests as a woman, a physician and a mother.

RESULTS

The

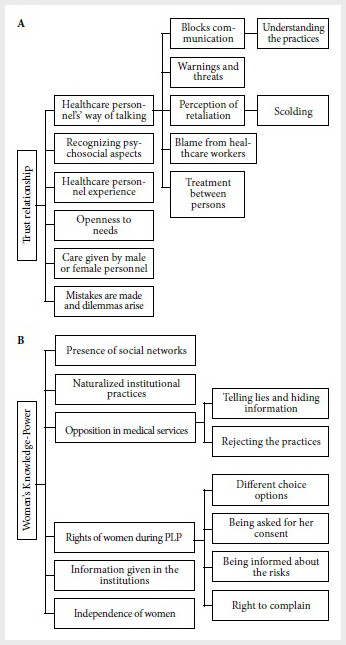

following two categories were found (Figure 1).

PLP: pregnancy, labor and postpartum

Figure 1. A. Trust relationship between

healthcare personnel and women. B. Women’s knowledge-power.

Trust relationship between staff and women (Figure 1A)

Building links between healthcare personnel and women requires

trust. This allows a therapeutic link to be established where women accept the

recommendations of the staff and there is adherence to the initiatives of the

health services. Confidence changes according to the aspects developed in Table 3.

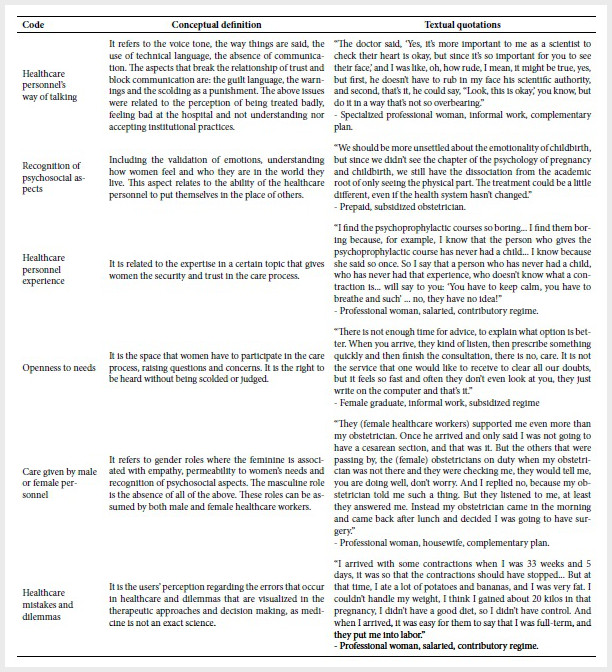

Table 3. Trust relationship category codes between

healthcare personnel and women

The participant observation showed that several

sexual and reproductive rights were violated in all the women participants,

which implies that obstetric and gender violence affects different social

classes. However, for women with a lower social class there are problems that

are intensified to a greater extent. For example, the lack of openness to the

needs of women and the lack of recognition of psychosocial aspects. In this

regard, the healthcare personnel treated the participants as if they were

ignorant and careless regarding their own PLP process. Women are scolded and

judged when medical protocols are not followed. The social context is not taken

into account since they are women who live in the most vulnerable localities of

Bogota and with few social networks (Table 1A), which reduces the use of

healthcare services. The pain in childbirth, breastfeeding, and medical

procedures is naturalized by healthcare personnel and there are no alternatives

to connect with women’s feelings.

Women’s knowledge-power (Figure 1B)

Women possess knowledge that they have built into their life

stories, through the social networks

that surround them and in health services. The way in

which this knowledge is constructed determines the power and decisions they

make in health institutions. The aspects related to this category are

developed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Women’s Knowledge-Power

Category Codes

Inequalities according to social class in the above aspects

include having different points of view

when faced with a medical recommendation and the right

to complain or demand for improvement. In these aspects, women with a lower

social class are affected more. In this regard, the participant observation

showed that the participants did not express their dissatisfaction with the

care provided, nor did they structure formal complaints in the health services.

When discussing this aspect with the women, they expressed fear of

confrontation and their rights acquired a connotation in favor of public

institutions. Similarly, there is a deficit of inputs and human talent in these

services, reducing the alternatives for choosing personnel trained in humane

practices.

DISCUSSION

The findings showed changes in the doctor-patient relationship,

taking into account that it is a social and intersubjective interaction, and it

results from its own socio-political context. There are structural factors that

determine the functioning of health systems under the concept of supply and

demand in the global market (25). The doctor-patient relationship

includes technological elements such as the use of the computer, which is

relevant for the registration of data and acquires a value above the

interaction of the subjects. Likewise, the relationship with the power of the

administrative sector is visible, which diminishes the freedom of the

professional to respond to the market economy, subordinating the ethics of the

healthcare personnel (25). In this research, this problem is part of the

structural barriers that institutions face in applying humanized practices in

PLP.

In this context, the relationship between subjects

is not important, but rather the results expected from the medical act.

Technology is also transformed, since it is no longer an aid but is central to

the structure of medicine. All of the above is more important than the patient,

and medical work becomes dehumanized in a socio-political context that

encourages this problem (25). In this research, technology acquires

a more important role than the signs and symptoms, and also than the accompaniment,

when it comes to physiological and natural childbirth.

The patient-doctor relationship is eliminated by

the institutional administrative agenda which is more important than the

doctor-patient agenda. In this context, care is depersonalized, and meetings

are automated. The doctor’s agenda is structured on the basis of the spatial

and temporal conditions of the medical practice. The space and time of this

consultation is defined by the institution from an administrative framework

that seeks to make medical management profitable. The doctor arrives in a space

for which he prepares in his medical training and is forced to apply his

biomedical knowledge in difficult conditions, since the time of consultation

and the administrative activities that he has to carry out by institutional

order eliminate the possibility of taking into account the socio-cultural

aspects of the HDP (26).

With regard to male and female identities, medicine

has historically been masculinized. This is visualized in the discourse of the

English medical society in the 17th century, where professionals are advised to

avoid contact and intimacy with patients. In the 19th century, the concept of

sympathy (understood as affinity between people who are attracted to each

other) is identified in Victorian society as feminine and unscientific, as are

doctor-patient relationships. In the United States, after graduating, some

doctors integrated sympathy into their work, but others advocated more in favor

of technology and separation from interpersonal relationships. These aspects

have influenced the fact that in the 20th century, sympathy, defined as skills

of an affective nature, has also lost its scientific value (27).

Ignorance of the history of the medical profession

allows this masculinization to persist today and the difficulties in integrating

theoretical and practical knowledge are understandable (27),

which affects the healthcare for health service users, since they transit

through health institutions where healthcare personnel work individually.

Violence against women in PLP has its origins in

medical training, where there are hidden agendas that are learned historically

in academic settings. There is a disassociating habitus on the part of

healthcare personnel who ignore the human character of women during labor, so

it is possible that disrespectful behaviors are validated. The authoritarian

habitus generates threats against women who do not follow medical orders,

blaming them when they do not “collaborate” (call for the norm) in the delivery

process and disqualifying the pain they feel. In the habitus in action, women

are seen as inferior from the professional and gender point of view, which is

relevant for the repressive rules that women accept in a subordinate way in a

context where suffering is supposed to be deserved and the social reality of

the population is ignored (28).

Gender related issues are observed across social

institutions (29) and health

services are no exception (30). In them, the related feminine and

masculine roles are established, giving an account of the hierarchies developed

at a social level (29,30). Women’s partners, present in the research, are

excluded from the care process, assigning the reproductive role exclusively to

women. However, men are included in the services when it is desired to impose

certain institutional practices on women. Autonomy in decision-making about

women’s bodies is determined by the presence of the child, in which the state,

health professionals and the father of the fetus play important roles.

Within the limitations, this research did not seek

to generalize as population studies traditionally do, but rather to understand

specific aspects of the problems raised in the research. A traditional

ethnography was not carried out, where the researcher lives permanently in the

field, but 13 months of observation were carried out, staying in the field at

least three days a week. The participant observation was carried out only by

the principal investigator, taking into account economic limitations. This researcher

is not an anthropologist, but a doctor from Bogota, who is part of the context,

and her vision could ignore other aspects that could be relevant in the

analysis of the information. However, this public health research has been a

collaborative work, where the support of social science researchers was

relevant, who helped to build a comprehensive vision of the medical issues to

be analyzed. It would have been possible for a greater number of people to

participate, in search of the excessive amount of information in relation to

social class, but given the established budget and schedule, more women could

not be invited to participate.

In conclusion, it is necessary to develop

interventions in educational and health institutions that take into account the

theoretical and methodological proposals of this research and the

democratization of medical information. Health inequalities and inequities are

preventable through public policies with a gender perspective that contribute

to transforming both the health and educational systems in Colombia. It is

necessary to study in depth the impact of the HDP on the quality of the care

process and to identify the different masculinities that play important roles

in women’s relationships with healthcare personnel.

Acknowledgements:

To the women and healthcare personnel who participated in the research. Fundación Arka, Organización Apapachoa, Movimiento Nacional por la Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en Colombia, Tribu Criarte, Secretaría de Salud Bogotá. To Marcelo Amable, Alfredo Maya and Monica Saenz for their contributions from the social sciences. To Universidad CES in Medellin and Colciencias for their funding.

REFERENCES

1.

Downe

S, Lawrie TA, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT. Effectiveness of respectful care

policies for women using routine intrapartum services: a systematic review.

Reproductive health. 2018;15(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0466-y.

2.

Organización

Mundial de la Salud. Prevención y erradicación de la falta de respeto y el

maltrato durante la atención del parto en centros de salud [Internet] Ginebra OMS; 2014 [citado 30 de

Enero de 2020]. Disponible en : https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134590/WHO_RHR_14.23_spa.pdf;jsessionid=8D5556D17EF46062AA6DDB21F34094F4?sequence=1.

3.

Monroy

MSA. El continuo ginecobs-tétrico .Experiencias de violencia vividas por

mujeres gestantes en servicios de salud en Bogotá [Tesis maestría]. Bogotá:

Escuela de estudios de Genero Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2012.Disponible

en: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/7805/1/soniaandreamonroymu%C3%B1oz.2012.pdf.

4.

Briceño

Morales X, Enciso Chaves LV, Yepes Delgado CE. Neither Medicine Nor Health Care

Staff Members Are Violent By Nature: Obstetric Violence From an Interactionist

Perspective. Qualitative health research. 2018;28(8):1308-19. doi: 10.1177/1049732318763351.

5. Vallana Sala VV. Parirás con dolor, lo embarazoso de la práctica obs-tétrica. Discursos y prácticas que naturalizan la violencia obstétrica en Bogotá [Tesis de maestría]. Bogotá: Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; 2016. Disponible en: https://repository.javeriana.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10554/19135/VallanaSalaVivianaValeria2016.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

6. Colón IC. Sentimientos, memorias y experiencias de las mujeres en trabajo de parto el caso de centros hospitalarios en Cartagena [Tesis de maestría]. Cartagena: Escuela de estudios de Genero Universidad de Cartagena y Nacional de Colombia; 2008. Disponible en: http://bdigital.unal.edu.co/53287/1/.candelariacoloniriarte.2008.pdf.

7.

Rocha-Acero ML, Socarrás-Ronderos F, Rubio-León DC. Prácticas de atención del

parto en una institución prestadora de servicios de salud en la ciudad de

Bogotá. 2019;37(1):53-65. doi: 10.17533/udea.rfnsp.v37n1a10.

8.

Jojoa-Tobar E, Cuchumbe-Sánchez YD, Ledesma-Rengifo JB, Muñoz-Mosquera MC,

Suarez Bravo JP. Violencia obstétrica: haciendo visible lo invisible. Rev Univ

Ind Santander Salud. 2019;51(2):136-47. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18273/revsal.v51n2-2019006.

9.

Bedoya-Ruiz LA, Agudelo-Suárez AA. Relación de las mujeres en embarazo, parto y

postparto (EPP) con los servicios de salud según la clase social. Rev Gerenc

Polít Salud. 2019;18(36). doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.rgps18-36.rmep.

10.

Breilh J. Las categorías causalidad y clase social como elementos de la

ideología epidemiológica. En: Breilh J, editor. Crítica a la interpretación

capitalista de la Epidemiología Un ensayo de desmitificación del proceso de

salud y enfermedad. Méjico: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana; 1977. P. 78-90.

11.

Breilh J. Breve recopilación sobre operacionalización de la clase social para

encuestas en la investigación social. En: Centro de estudios y asesoría en

salud (CEAS), editor. Quito: Ecuador Centro de estudios y asesoría en salud (CEAS);

1989. p. 1-12.

12.

Menéndez EL. El modelo médico hegemónico. Estructura función y crisis. En:

Menéndez EL, editor. Morir de Alcohol: Saber y Hegemonía Médica. Mexico DF:

Alianza Editorial Mexicana; 1990. p. 83-117.

13.

Menéndez E.L. El punto de vista del actor: homogeneidad, diferencia e

historicidad. En: Menéndez E.L, editor. La parte negada de la cultura:

relativismo, diferencias y racismo. Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra; 2002. p.

291-365.

14.

Grondin J. Que es la interpretación. En: Grondin J, editor. El Legado de la

Hermeneutica Primera ed. Cali: Universidad del Valle; 2009. p. 15-36.

15.

Packer M. La investigación enmancipadora como reconstrucción racional En:

Packer M, editor. La ciencia de la investigación cualitativa. Bogota,

Universidad de los Andes: Facultad de Ciencias Sociales; 2013. p. 337-363.

16.

Kincheloe J, McLaren P. Replanteo de la teoria critica y de la investigación

cualitativa. En: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS,

editores. Manual de investigación cualitativa Volumen II Paradigmas y perspectivas

en disputa. Barcelona: Gedisa; 2012. p. 241-91.

17.

Scheper-Hughes N. Nervoso. En:

Scheper-Hughes N, editor. La muerte sin

llanto Violencia y vida cotidiana en Brasil. Barcelona: Ariel; 1997. p.

167-212.

18.

Mendizabal N. Los componenentes del diseño flexible en la investigación

cualitativa. En: Vasilachis de Gialdino, editor. Estrategias de investigación

cualitativa. Barcelona: Gedisa; 2006. p. 65-103.

19.

Galeano ME. Diseño de proyectos en la investigación cualitativa: Fondo

Editorial Universidad EAFIT; 2004. p. 11-81.

20.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Perfil sistema de salud en Colombia.

[Internet] Washington, D.C: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2010 [citado

30 de enero de 2020]. Disponible en : https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/Perfil_Sistema_Salud-Colombia_2009.pdf?ua=1.

21.

Restrepo ODA. Vigencia de la categoría clase social en salud pública. En:

Estrada M J H, editor. Teoria Critica de la Sociedad y Salud Publica. Bogotá:

Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Universidad de Antioquia; 2011. p. 134-44.

22.

Fontana A, Frey JH. La entrevista. En: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editores. Manual de

Investigación Cualitativa Volumen IV Métodos de recolección y análisis de

datos. Barcelona: Gedisa, 1ª edición; 2015. p. 140-189.

23.

Evens TMS, Handelman D. Introduction: The Ethnographic Praxis of the Theory of

Practice. Social Analysis [Internet] Brooklyn NY: The International Journal of

Social and Cultural Practice; 2005 [citado el 30 de Enero de 2020]. Disponible

en :

www.jstor.org/stable/23179071.

24.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y

procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Medellin: Editorial

Universidad de Antioquia Facultad de Enfermería de la Universidad de Antioquia;

2002 .p. 3-197

25.

Rossi I. Capítulo 2. La clínica como

espacio social. Época de cambios o cambio de época?. En: Hamui Sutton L, Maya A

P, Hernández Torres I, editores. La comunicación dialógica como competencia

médica esencial. Ciudad de Mexico: Manual Moderno; 2018. p. 38-58.

26.

Cruz Sanchez M, Hernández Torres I, Grijalva MG, Maya A P, Dorantes P. Capitulo

3. El ejercicio de la profesión médica y la comunicación médico paciente en

contextos situacionales. En: Hamui Sutton L, Maya A P, Hernández Torres I,

editores. La comunicación dialógica como competencia médica esencial. Ciudad de

Mexico: Manual Moderno; 2018. p. 58-100.

27.

Ortiz G T. El género, organizador de profesiones sanitarias. En: Miqueo C,

Tomas C, Tejero C, Barral M J, Fernandez T, Yago T, editors. Perspectivas de

Género en Salud Fundamentos Científicos y Socioprofesionales de Diferencias

Sexuales No Previstas. Madrid: Minerva Ediciones, S.A; 2001. p. 53-77.

28.

Castro R. El habitus en acción. La atención autoritaria del parto en los

hospitales. En: Castro R, Ervite J editores. Sociología de la práctica médica

autoritaria. Violencia obstetrica, anticoncepción inducida y derechos

reproductivos. Cuernavaca, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico;

2015. p. 81-131.

29.

Connell R, Pearse R. Gender theorist and gender theory. En: Connell R, Pearse

R, editors. Gender In world perspective 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2015.

p. 68-206.

30.

Lorber J, Moore LJ. Hierarchies in helath care: patients, professionals and

gender. En: Lorber J, Moore LJ, editors. Gender and the social construction of

illnes. Lanham: Altamira Press; 2002. p. 37-51.

Sources of funding: Colciencias National Doctoral Scholarship calling 647-2014 and Small Amount Calling from Universidad CES in Medellin, Colombia.

Citation: Bedoya-Ruiz LA, Agudelo-Suarez AA, Restrepo-Ochoa DA. Relations

established by women during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum with health

personnel according to social class in bogotá: qualitative study. Rev Peru Med

Exp Salud Publica. 2020;37(1):

7-16. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4963

Correspondence to:

Libia A. Bedoya-Ruiz; Escuela de Graduados, Universidad CES,

Medellin, Colombia; Calle 10 A No. 22 – 04. Medellin, Colombia;

bedoya.libia@ces.edu.co,

bedoyalibia@hotmail.com.

Authors’ contributions:

All

authors participated in the conception, design of the work, analysis, data

interpretation, critical review and approval of the final version. LABR carried

out the data collection and initial writing of the article. All authors are

responsible for all aspects of the manuscript and warrant its content. This

article is part of LABR’s doctoral training process in the PhD in Public Health

at Universidad CES and will be used as part of the material used for the thesis

dissertation.

Conflicts of interest:

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Received:

14/11/2019

Approved:

05/02/2020

Online:

23/03/2020